Submitted Review

Claire Healy, Sean Cordeiro ‘You Are Here’

‘You are here’ is both a familiar and nostalgic turn of phrase, suggesting old billboard maps at the entrance to theme parks as well as the blue bead on your screen that draws a thin thread from the earth to several satellites. This combination of whimsy and mobilising technologies sits at the heart of Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro’s exhibition, which playfully reinvents the day-dreamer’s original tether: the kite. Using salvaged parts of Australian Air Force planes, Healy and Cordeiro have transformed military detritus into expressive flights of fancy with Japanese folkloric designs.

Healy and Cordeiro have patiently created these fantastical contraptions during what they term the ‘Iso-Age’, when almost all of our flying machines have been grounded. These works muse on the sudden, shuddering end to a typically itinerant contemporary lifestyle, which has left the artists unable to attend a residency in Niigata, Japan, where competitive kite flying is a pastime that reaches back to the Edo period. Knowing this, the works in ‘You Are Here’ become tokens of yearning, alluding to an era of inertia.

‘This taxonomy engulfs every inch of the wall, theatrically off-balance.’

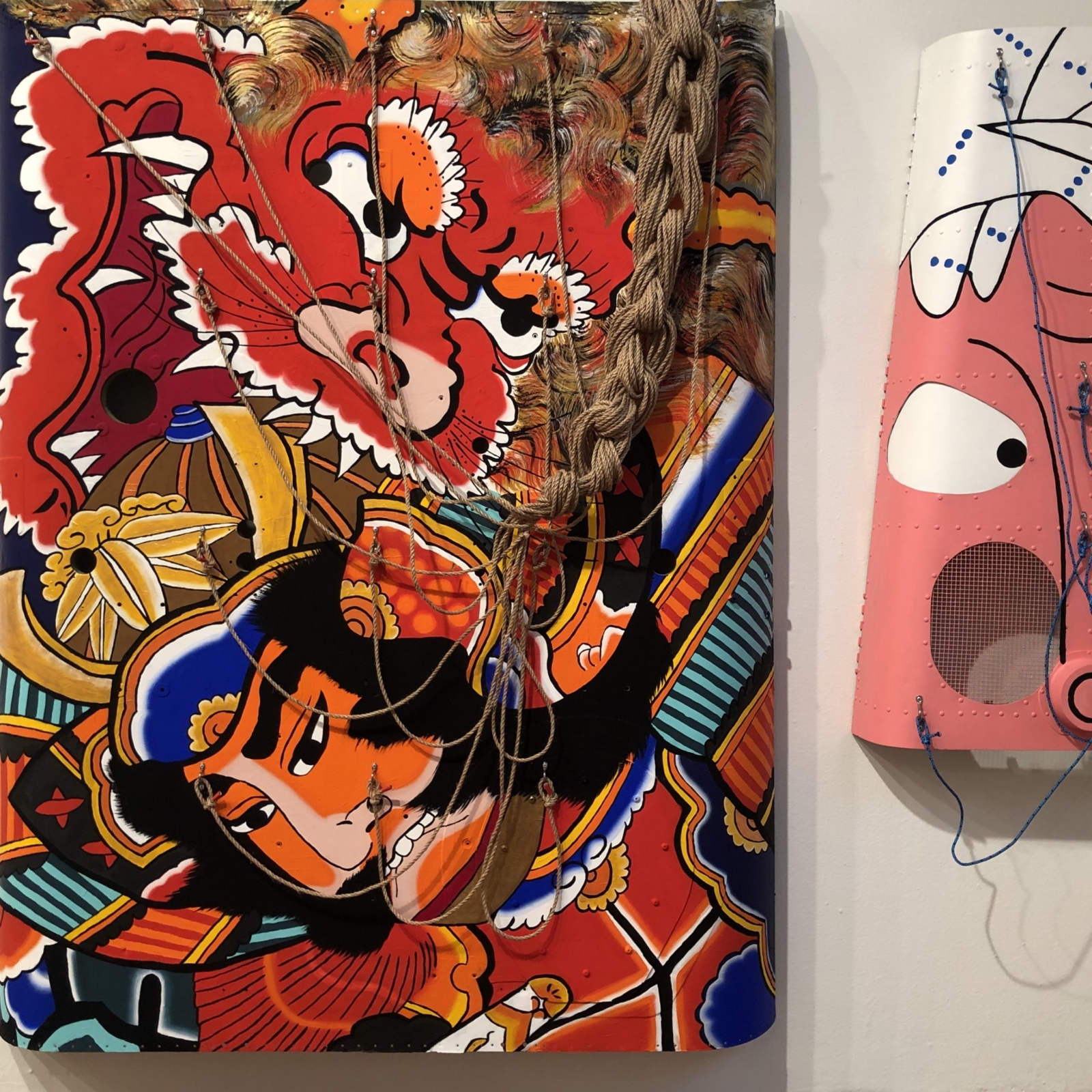

As you enter the room, you are confronted with a wall of static kites, splayed and pinned like butterflies on a board. This taxonomy engulfs every inch of the wall, theatrically off-balance. Without a breath of wind in the second gallery space of Roslyn Oxley9, our focus is instead funnelled towards the distinctive faces of warriors and demon oni, a smiling cat, and the bulking body of a carp with mechanical bowels, nosediving into the floor. In this vivid but orderly hang, Healy and Cordeiro surrender the free-wheeling frenzy of kites in action for dramatic inaction.

The designs on these aeroplane panels, doors and cowlings efface their original military use – except perhaps the Gashadokuro skeleton painted dextrously onto the pointed nose plate, recalling decorations on warplanes for levity and luck. The Gashadokuro spirits are even rumoured to possess the power of invisibility and indestructability, revealing Healy and Cordeiro’s wry matching (and mismatching) of functions.

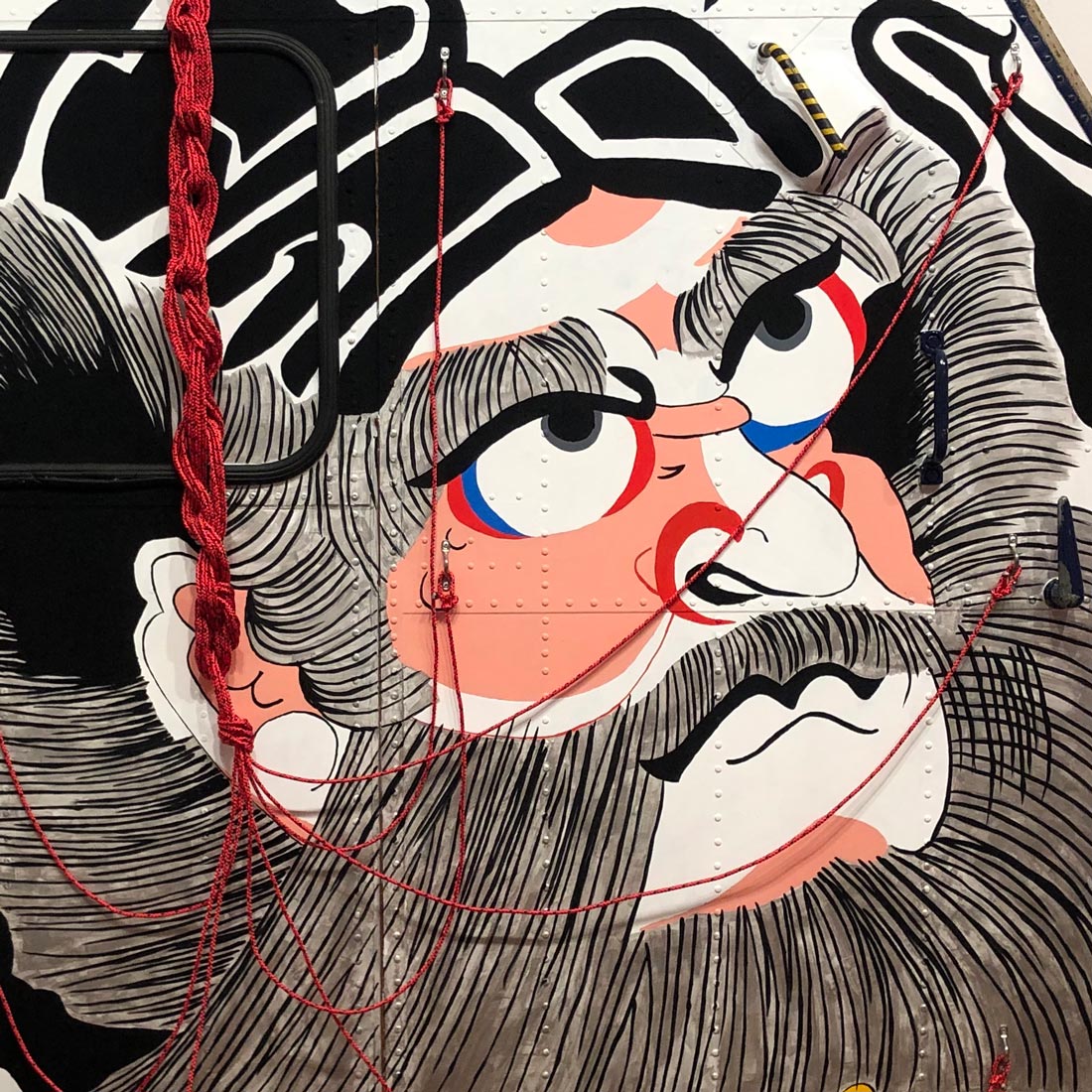

The magic and tangle of the painted surfaces are fastened with kite ropes that hang loosely in anticipation. These ropes find playful anchor points, piercing the eyes of the scowling Daruma in a way that alludes to idols coming alive when their eyes are ‘opened’ by priests. (More irreverently, air vents and apertures on other works act as kabuki mouths and eyelids.) Entwined ropes cowlick over the panel depicting Raiko and Shuten-doji, doubling as an unruly braid over the demon’s shoulder. The threads then part and are pinned purposefully across the surface, reminiscent of body piercings, connecting the combatants in an intimate tussle. These lines are almost cartographic, mapping out routes across faces and folktales through whimsical skeins.

Consider the strength it would take to hold the reins of this plane flank, buffeted by strong winds. With enough gusto and meteorological luck, would it become airborne? The robust metal ‘skin’ of each kite would struggle to gather enough lift. And yet, they come alive through contorted faces painted in the vibrant, heavily-outlined ukiyo-e style – arresting the floating world.

Within our hyperconnected yet hyper-isolated world, these kites have the feeling of an emergency artwork – if in distress, whip this off the wall and use it to escape. Historically, kites have been used to deliver messages to a lover or deity, ward off evil, research scientific phenomena, wish for benevolent weather and conjure child-like delight. As we all wait for our next flight out of here, these kites are a lightning rod for the imagination.

No Comments