Submitted Review

‘Ultimately, it’s a comment on the futility of unquestionably doing things the way we always have.’

Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa ‘Half Empty Half Double’

“If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, The Leopard 1958

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Albert Einstein/ Max Nordau Degeneration 1895

These often mis-attributed quotes and others like them have become ubiquitous recently. They’ve been used in connection with Covid, climate change and other issues.

With climate change, the widening realization that more action is now urgent makes us confront how we might change the ingrained habits built up over five generations since the Industrial Revolution.

Habit – or unthinkingly, inanely, continuing to do things the same way each time – can make life easy, as it does when driving a car. But it can be a brake on progress. If we are intelligent, we’ll question our habits. The mindlessness of habit is one theme that arises in Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa’s current show at CHAUFFEUR in Sydney’s Liverpool Street until December 11.

The exhibition, Half Empty Half Double, includes a performance in the form of a video, a vibrant large-scale wall-work, and a new series of geometric drawings in precisely constructed rhomboid frames.

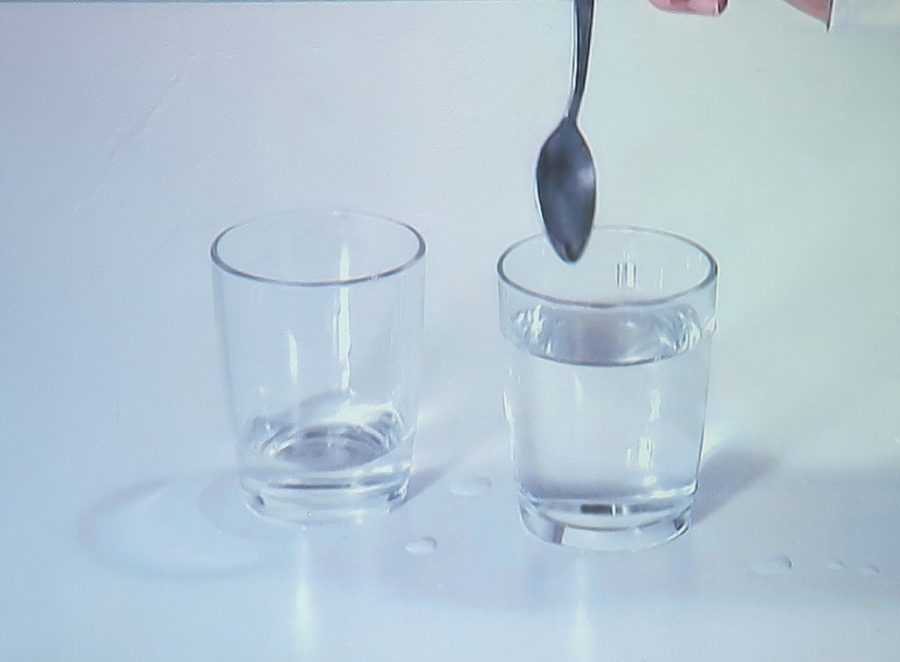

In the performance video a white shirt-sleeved hand repetitively transfers water from one drinking glass to an adjacent one with a teaspoon. Rather than dwelling on the preciousness of water, the achingly slow progress toward the end goal can make the viewer ask “Why do this?” and consider alternative ways to achieve the result. Ultimately, we are hypnotically drawn to look for small changes that might occur in the mechanical process; then we mentally mark the point where two glasses are half full and half empty at the same time; and then we anticipate the completion of the transfer, when the full glass will become empty at the end. The ‘have’ becoming a ‘have not’ and the meek inheriting the earth’s water supply, perhaps. As if.

Yes, there are parallels to draw between this performance and many aspects of life. Ultimately, it’s a comment on the futility of unquestionably doing things the way we always have. But there’s a twist at the end of this visual story: ultimately the process never reaches its goal … actually, can never reach its goal. As the water transfer nears finality, the steepness of the glass prevents the spoon from lifting the final drops. Viewing this as a scientific experiment, it demonstrates that repetition of a process that seems to work at the start may slow down and ultimately end in failure. Well may we ask: ‘Will our climate action plan fail at the final stage?’, ‘Will arms build-up maintain equilibrium or end in destruction?’ or ‘Will continued land-clearing feed the world, or in the end destroy it?’ So Rodrigues de Sousa’s performance can become a warning for us to question many of the processes we now take for granted.

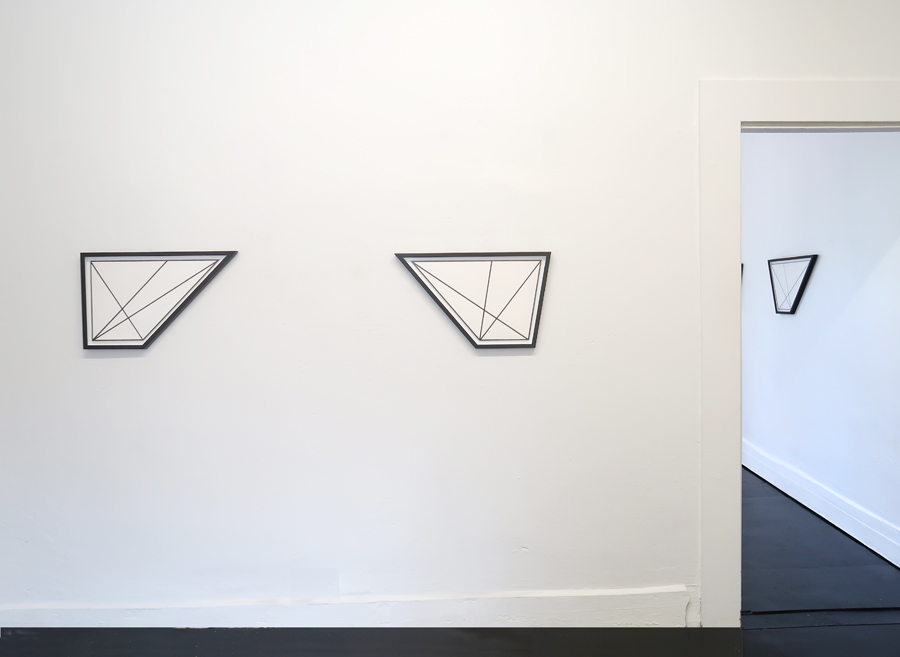

The deceptively simple, but perfectly drawn, Double Variations drawings in the show conjure up other thoughts.

Here, Euclidian forms drift from ancient Greek teaching to the role they have played at the heart of Constructivism and geometric abstraction since Kazimir Malevich’s hard-edged black square.

Rodrigues de Sousa selects Euclid’s Proposition 41 Theorem from the original mathematics master’s Elements Book 1: ‘If a parallelogram and a triangle are on the same base and in the same parallels, the parallelogram is double the triangle’.

By eliminating the explanatory theorem and all other labelling, Rodrigues de Sousa leaves us to ponder the lines and shapes. Studying such a simple image for the time that we might spend on a more complex painting, the combination of parallelogram and triangles takes on a rabbit-duck illusion morphing. Which triangle is half the size of the largest? Which one is the largest? Can the diagram be interpreted as three-dimensional?

Finally, we return to the glorious wall-work that confronts the viewer on entering the gallery, Proposition: Equivalency(2021). It’s an image that could work at any scale; a splintering of primary colours in yacht-like shaped canvases with a dominating parallelogram. Actually, it’s a presentation of a page without words from the illustrative book The First Six Books of The Elements of Euclid edited by Oliver Byrne in England, 1847. This beautiful but obscure book was the first one to use elementary colours to assist in understanding geometry, and it was an important influence on the appearance of the De Stijl movement in 1917. So it has particular importance to the artist, who earlier taught geometry.

The exhibition catalogue is at http://www.chauffeurgallery.com.au/index.php

Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa’s intriguing work at https://nunorodriguesdesousa.net/works/

No Comments