Submitted Review

'Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize'

‘You could throw a rock in almost any direction and smash something elegant.’

Why talk about sculpture when I can photograph it?

Constantin Brancusi (1876 – 1957)

The twentieth anniversary of the Small Sculpture Prize opens at Sydney’s newest public art gallery, Woollahra Gallery at Redleaf. With past winners on display, it is a prize that represents a fantastic developing catalogue of sculptural imagination in the 21st century. You could throw a rock in almost any direction and smash something elegant.

Designed by Frederic Moore Simpson in 1897, the newly renovated building is exquisitely configured to fit the definition of a contemporary art space while holding the beauty of the original historic building at its heart. The artwork could not look better. With pure white walls and a large expanse of near floor-to-ceiling windows lining the upper gallery, both the natural lighting of the space and the fitted fixtures delight, highlight and define. St Brigid’s once heavy dark wooden door frames have also been painted, and some of the beautiful original panelling has been retained. On the rainy Sunday afternoon when I visit, curator and gallery coordinator, Sebastian Goldspink, and taste-maker and art advisor, James Dorahy, extend the idea of home in the way that they welcome people.

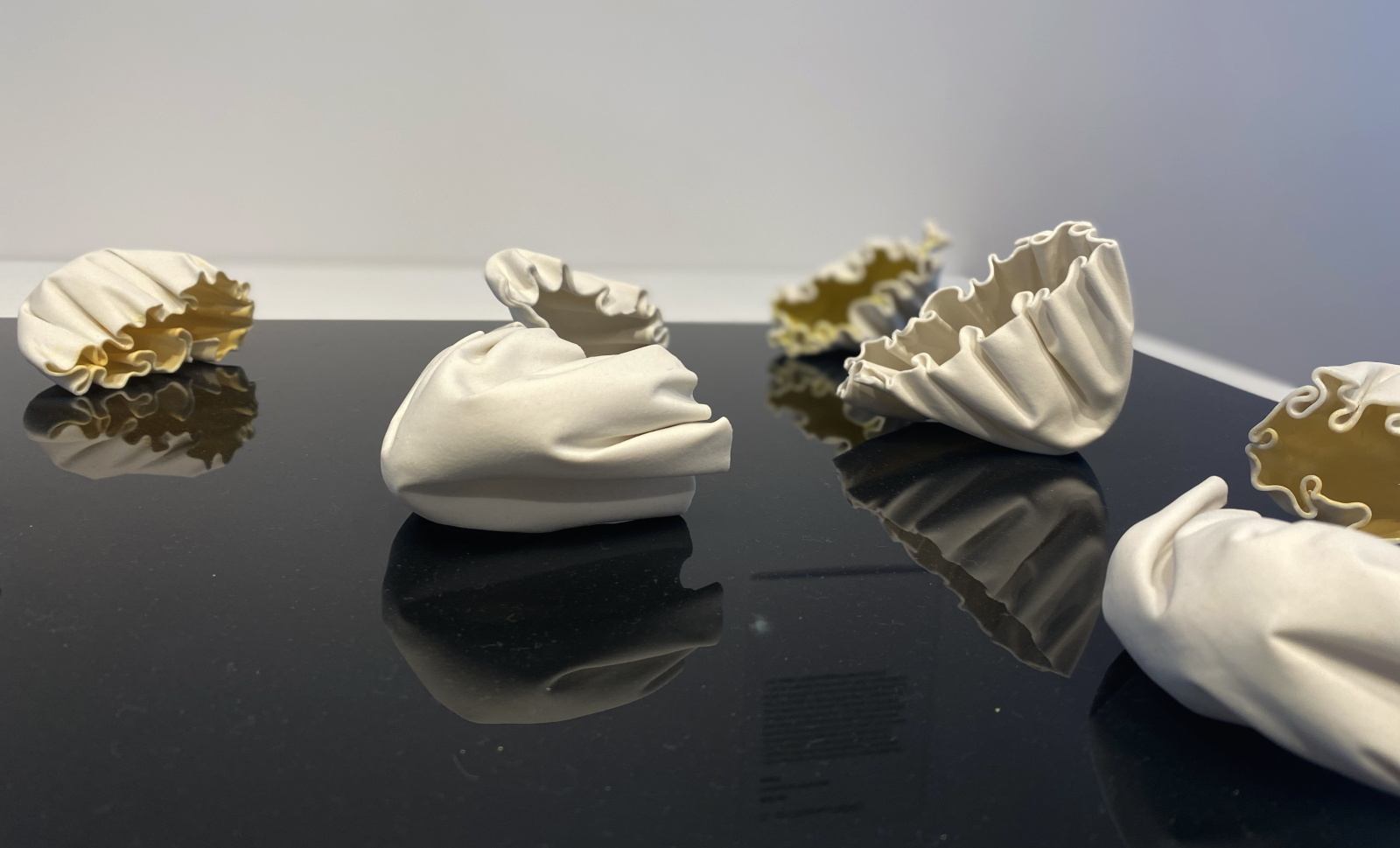

The old house, devoid of all else and filled with these tiny sculptures, takes on an atmosphere of stillness. The sculptures become scholar’s objects, mediative and serene, their opinions and aesthetic qualities present in every room. Stillness, a familiar attribute of sculpture, allows us to contemplate each object’s form. Several internal windows have been silenced, cleverly bringing seclusion. Nothing in St Brigid’s seems distracting or untidy.

In the first room to your right as you enter the gallery, there are tiny trees, so many trees in fact that the tree becomes as much a fundamental shape of the geometry in here as the cylinder, the sphere, or the onduloid. While it may not be vigorously contemporary, there is nothing unpleasant about this. To paraphrase Robert Hughes (am I?), Australians rely on nature in lieu of a real art tradition. Geometry, from the Greek ‘metria’ meaning ‘a measuring of’ and ‘ge’ meaning earth or land, the once-great art is still great, greater still. St Brigid’s is a place to study the architecture of the particular, like a botanist.

Some of the small sculptures are underpriced. Others are overpriced. Some are both. Joanna Capon spoke with eloquence on the judges’ decision to award the prize unanimously to a piece that brought joy in straitened times. Rhonda Sharpe’s ‘Desert Woman with Moustache, Coolamon and Pretty Clothes’ is a totem of bounty, of vibrant threads and good luck, of bush food and good hunting.

So often, regarding sculpture, our thoughts turn to attachment, to the weighted balance. Whether metaphorical or actual, wondering how this thing remains standing has always been part of the game. Implausible gravities, such as are found in Stuart McLachlan’s ‘Cardinal Sins’ with the church on the sandstone precipice, remind us how close we have come to the edges of ourselves lately. Sculptors play to our corporality by association with human positions: this one is lying down; this one is leaning; this one is about to fall. When the sculptures are small, we may be godlike by comparison and allowed a god’s eye view. A contemplation of structure involves an awareness of tension and the degree of effort implied by the pose.

When considering the field of small sculpture and the role that small objects play in the study and history of art and culture, we are looking at a delicate realm of powerful artifacts that have not been toppled. The symbology of the ancient tradition of memorialising bronzed leaders on horseback is ‘Usurped’ by Rodney Pople. Upon a classical plinth, an upside-down Pinocchio rides an upside-down horse.

Unlike the Archibald Prize where artists tend to push themselves to work on the largest of all possible heads, supersizing their canvases to get noticed in the squeeze, artists accustomed to public commissions often downsize the scale of their work for the Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize to meet the 80 centimetre requirement. To miniaturise is to domesticate. Some of these sculptures are so tiny they might have been made by elves. I leave thinking of Edmund de Waal and his appreciation for those small carved Japanese netsuke: ‘this is a good place to put something in your pocket and begin to start a journey.’ I wonder if the old pond in the gardens that we danced around as children when St Brigid’s was a library is still alive with tadpoles. Apparently, it is.

No Comments