Submitted Review

The.LongBoard: 'Tarnanthi 2021' by Eleen M Deprez & Michael Newall

‘The exhibition sheds light on the work and gives space to artists so that their stories can emerge and be seen.’

Tarnanthi (Kaurna language, meaning ‘come forth or appear – like the sun and the first emergence of light’; pronounced ‘tar-nan-dee’) is an annual event, presenting contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art from across Australia. Its roving spotlight picks out trends, developments and personalities within the constantly developing universe of Aboriginal Art. Every two years Tarnanthi expands into two parts: the core exhibition at the Art Gallery of SA (AGSA), and a substantial constellation of projects at other Adelaide venues and regional galleries. There are some significant and important shows that should be seen as part of the broader Tarnanthi experience. Standouts include: Water Rites, at ACE Open, curated by Danni Zuvela and focusing on issues around the significance of water; Troy-Anthony Baylis’s refigurations of queer history at Hugo Michel Gallery; and Pepai Jangala Carroll’s superb ceramics and paintings at the Jam Factory.

This review focuses on Tarnanthi at AGSA, which itself is a large, carefully organised and wholly satisfying showing of work. The artists here are drawn together by Tarnanthi’s Artistic Director Nici Cumpston. “This year,” Cumpston observes in her catalogue essay, “sees an emergence of painting that completely defies expectations.” It is the paintings, many brilliantly coloured, and in a wide variety of styles, that set the tone. Huge sweeping brushstrokes, traditional and pop elements melded together, and riotous combinations of patterning all signal a maximalism that does indeed defy expectations. It’s exciting and intoxicating – overflowing not only with paint and colour, but with formal invention, and conceptual innovation.

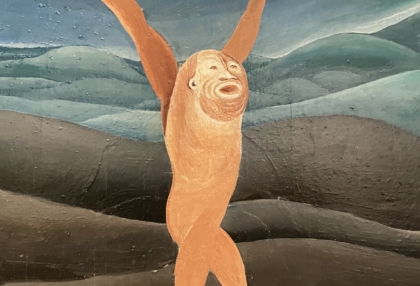

Heading downstairs at AGSA, where Tarnanthi takes up the entire floor, visitors are greeted by a bullock skull painted with neon-bright orange and blue stripes. The face is decorated with a snake struggling in vines. The work is by John Prince Siddon (Walmajarri people). Theatrically lit, it seems almost to pulsate, like something out of a fever dream. It is a suitably intense introduction to the large presentation of Siddon’s work here, and, indeed, to Tarnanthi as a whole. Siddon describes his work as, “all mixed up”, a formal and conceptual logic that carries through his sculptural and painted work. In his paintings, forms meld and melt into one another, traditional motifs from Country combining in a frantic, rhythmic motion, with images of contemporary political subjects. In the painting Mix it all up, creatures and people encroach on a sky-blue body of water, shaped like the Australian mainland. Four distressed-looking refugees approach, seemingly adrift, in a vessel labelled “boat people”. A larger ship bears a flag or sail, decorated with a Union Jack that is metamorphosing into a redback spider. A lone person, holding a spear as they stand in a canoe, is chased or swallowed by a shark. A large wall is covered with a repeating vinyl print (a patterned detail from the artist’s painting, Fear). On it are displayed wallaby skins, their thick grey fur framing shaved cartouches patterned and painted with images of animals. The experience fully immerses the viewer in Siddon’s wildly-coloured, shimmering vision.

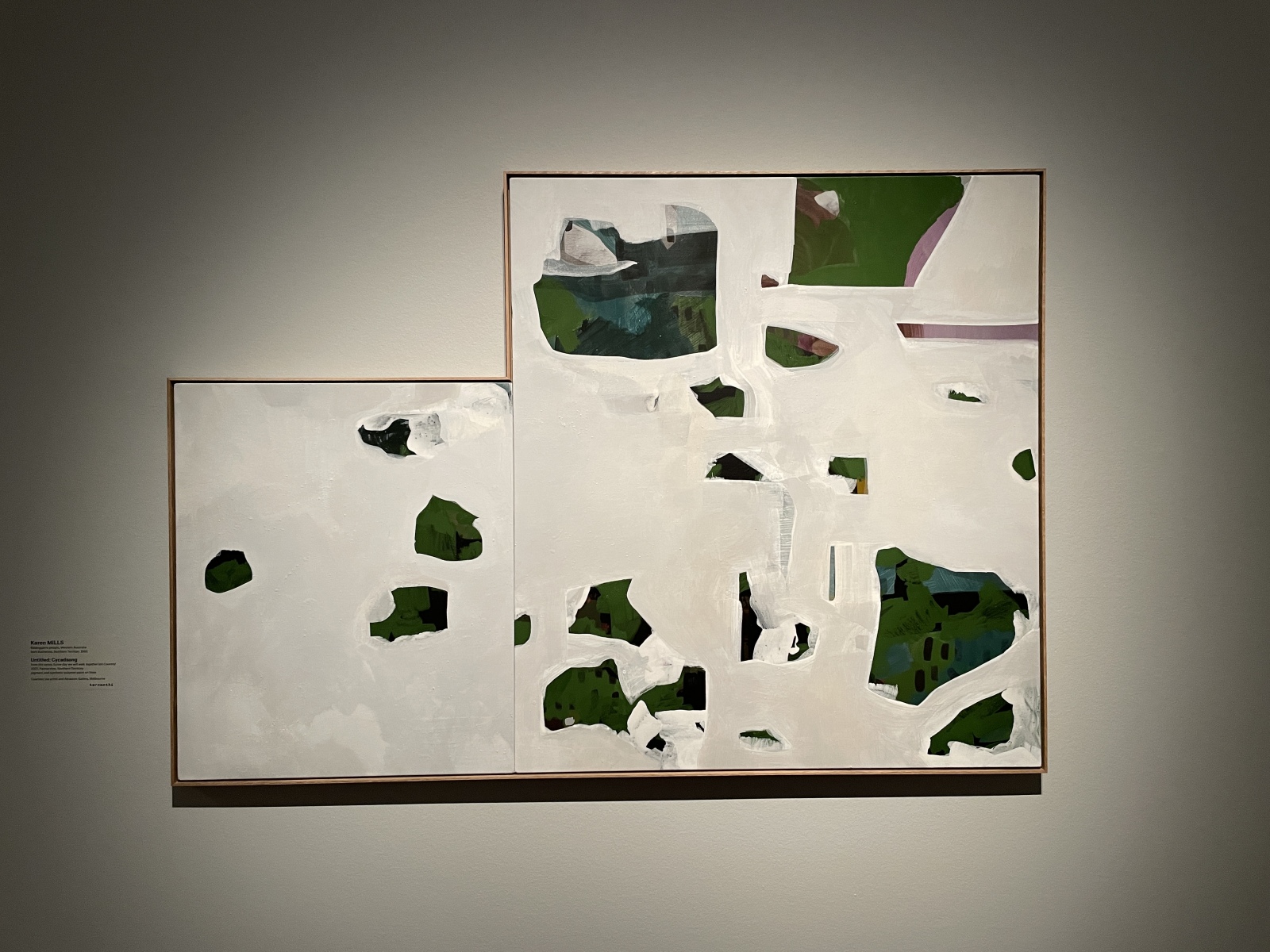

Karen Mills (Balanggarra people) pairs her canvases making large L-shapes. Layers of paints thinly overlap and intersect, speaking covertly of her themes of dispossession and displacement. In Mills’ paintings, things seem to appear and disappear, like clouds passing over a landscape or mist sweeping over the ground. Mills, a member of the Stolen Generations, has spoken about her work as a reflection on identity and feelings of connectedness and displacement as a Balanggarra person. The surface of the canvases reveal and resolve this tension: silky thin swathes of transparent white paint cover or wash over crusted, rough pigmented elements.

Kaylene Whiskey (Yankunytjatjara people) makes work that is enthralling. She merges pop culture with a celebration of Country. Her Seven Sistas Sign, painted on an obsolete tourist road sign, is a humorous play on the Seven Sisters, a significant Tjukurpa for many of Australia’s first peoples. Whiskey’s seven sisters are some of her personal idols: Dolly Parton, Tina Turner, and Cat Woman, among others. Rather than outrunning the advances of the Jampijinpa man, these sistas are preparing for the party that black Wonder Woman is throwing at 6 o’clock. In three minutes of Kaylene TV, an accompanying video work, the characters are brought to life, their painted forms animated and voiced by Whiskey. The eclectic pantheon of strong women make themselves at home in Anangu culture, and hang out with Whiskey; it is absolutely joyous.

In a small room in AGSA’s upstairs galleries, we meet the eyes of Jacob, photographed by Maree Clarke (Yorta Yorta / Wamba Wamba / Mutti Mutti / Boonwurrung people). Jacob wears reed necklaces of which enlarged versions, with feathers, glass objects, and teeth, are displayed in the room. River reed necklaces, once given to visitors passing through Country as a token of friendship, are here larger than life. This “super-sizing” reflects, Clarke says, “the scale of the loss of our knowledge and cultural practice”. As objects, they dominate the space, and one can read them as a threatening presence, like heavy chains hanging in a dungeon. But they are also beautiful objects, their size drawing attention to their delicate natural materials and forms .

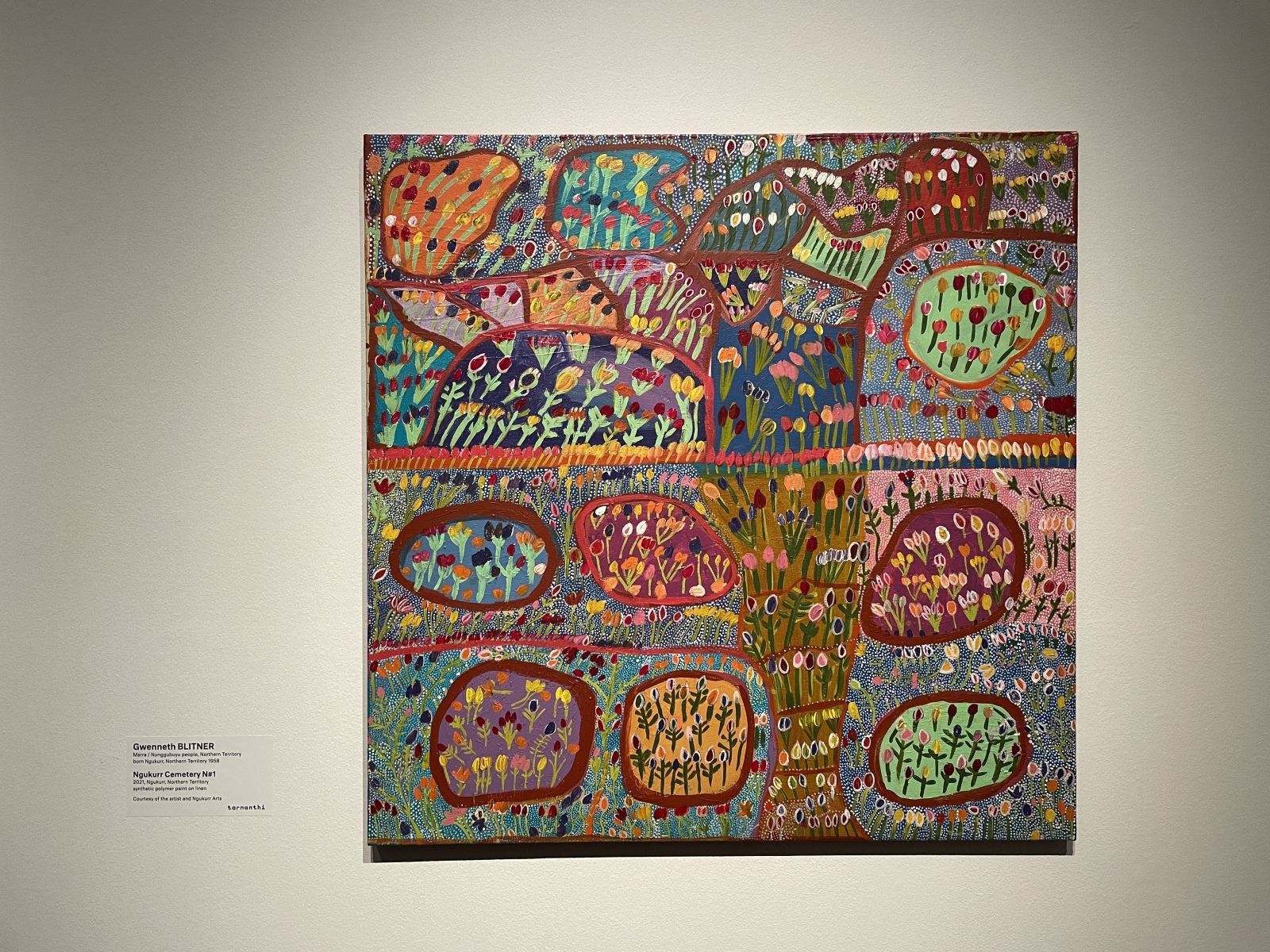

There is much else that we could linger on. Gwenneth Blitner (Marra/Nunggubuyu people) paints the abundance of flowers that bloom after the rains sweep through her Marra Country. Lillies are dotted around flush billabongs, wild bananas and other flowers are clustered around the hills, roads, and waterholes. Her paintings throb with colour, arranged into jauntily haphazard tapestries and patchworks of paint. Djerrkngu Yunupingu (Yolngu people) paints haunting mermaid-like beings, their uncannily sharp teeth perhaps scaring the viewer at first but they are friendly spiritual portrayals of personal events in the artist’s life. Timo Hogan (Pitjantjatjara) impresses with his monumental Telstra Award winning painting of Lake Baker. The salt lake is rendered in brushy white strokes bounded by black, conveying a sense of stark beauty and vastness. Gail Mabo (Piadram clan) presents a bamboo star map, Tagai, a huge version of the traditional maps of constellations used in navigation. This extraordinary object hints at the sublime among the mundane, and includes the star named for her famous father, Eddie Mabo.

Kent Morris (Barkindji people) shows a 10 metre wide projected moving image Barkindji Blue Sky-Ancestral Connections #10 is a kaleidoscopic slowly twirling video of corellas taking flight against elements and segments of suburban architecture. The geometric forms mirror, slowly revolve into changing patterns reminiscent of ceremonial markings. The sequence moves smoothly and whilst the intense blue of the sky startles one into attention, the interchanging patterns mesmerise as much as they hypnotise.

Tarnanthi at AGSA is not curated in the sense of arranging works according to an overarching narrative or thematic groupings, as such it embodies and stays true to the meaning of tarnanthi as a ‘coming forth’. The exhibition sheds light on the work and gives space to artists so that their stories can emerge and be seen. Throughout the exhibition there are however curatorial interventions that reinforce the works and stage thoughtful interactions between them. The salon-style hang of Tiwi papers comes to mind here. Close to 145 works by 65 different artists, all unframed and on uniformly-sized sheets of thick paper, are placed five rows high. The label tells us this is to approximate the impact of the singing and dancing of traditional Tiwi performance. Natural earth pigments and ochre tones hold sway in this room, and as we try to take in this sumptuous trove of painting, the works feel as if they rise up around us, looming and towering, like a soaring vortex. The hang brings out shared features but also draws attention to individual styles. Kaye Brown (Tiwi people) paints traditional Yirrinkiripwoja (body paint) designs using a Kayimwagakimi, a comb-like instrument carved from wood. Alfonso Puautjimi (Tiwi people), paints what is around him everyday: a bicycle, a ship, a still life grouping of his own sculptural work, paint pots. Well-known artist Timothy Cook (Tiwi people) paints concentric forms representing the Kulama (yam) ritual , initiating boys into manhood. His images here show a supple gestural strength and intensity.

Our last stop is the conceptual exhibition-installation, Through the Psychoscape, by Julie Gough (Trawlwoolway people). This has a quite different character from the other works in Tarnanthi. Gough turns a sharp eye to AGSA’s historical Tasmanian collection, selecting art and artefacts and curating them in relation to her own artwork. Among other historical objects, there is a chair attributed to the enigmatic Jimmy Possum, a Regency day bed, colonial landscape paintings by John Glover, William Piguenit and Eugene von Guérard, a grotesque phrenological caricature of a young black boy, and a musket. These objects are placed in relation to Gough’s own works. Next to von Guérard’s painting, showing a waterfall on the Clyde River, Gough projects a video work showing the same subject. In the video, the waterfall roars, taking at times the same perspective as the painter, but also hovering over the landscape, fully displaying its richness of colour, topography, and flora. Gough’s installation is dominated by a starkly-lit object: dangling from an upturned chair suspended from the ceiling are small, cut-out figures that create vivid silhouettes on the adjacent wall. The shadow figures, as they move about, suggest shocking narratives of violence and trauma. They are explicitly reminiscent of the figures in a famous print displayed nearby, the so-called Governor Davey’s Proclamation, an illustration used to explain to Tasmanian First Peoples the retributive justice to which they were now subject. Gough’s work, through these juxtapositions and interventions is a powerful decolonial project, vividly rewriting an idyllic and naive version of art history. As she writes in the catalogue: “visiting places depicted in colonial art, our lands accrued by outsiders, is like walking through a crime scene.” Visiting the usual displays of colonial art in our state galleries, she might well add, can be like seeing a crime covered up.

Tarnanthi, as a coming forth, is also an uncovering, not only in Gough’s sense, but also in the sense of making visible an extraordinary efflorescence of culture. Experiencing that will naturally engender other trains of thought. That is summed up better than we can say by senior Kaurna man Mickey Kumatpi O’Brien, who in the Welcome to Country for Tarnanthi said “when our people share culture, we believe you receive culture, and through the works of art you support the ongoing connection. … Ngaityu yakanantalya, Ngaitya yungantalya Padni-adlu wadlu which is saying that we are all brothers and sisters, that when we walk, when we sit, when we observe and listen to the land we connect and it connects with us and therefore we have the responsibility to look after it.”

Ea

Eleen M Deprez and Michael Newall

Images:

1. & 2. John Prince Siddon

3. Karen Mills

4. Kaylene Whiskey

5. Gwenneth Blitner

6. & 7. Tiwi Installation

8. Julie Gough

No Comments