Submitted Review

‘…the works together emit a frugal, almost Arte Povera vibe.’

Project 10: Section BB

Not bigger than a two car garage, and located in the sleepy south-west corner of Adelaide’s city centre, South West Contemporary is a relative newcomer to the city’s art scene. The gallery has a distinctive mission. Its director, artist Craige Andrae, aims to revive aspects of the dynamic 1990s Adelaide art scene, now somewhat faded into obscurity. Reminiscing about exhibition openings in the ’90s – when Andrae himself was the enfant terrible of the Adelaide’s art world – he wistfully recalls how artists of different generations gathered and connected. With the seismic shifts in Adelaide’s artworld of the past few years, those intergenerational connections now seldom occur. The ten exhibitions South West Contemporary has presented since opening in March 2019 have been intended to recreate something of that dialogue, showing art by recently-graduated artists alongside the work of an older generation of artists who are Andrae’s peers.

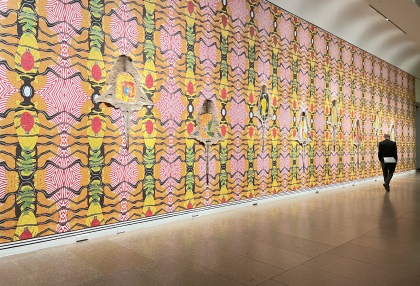

Currently on show is Project 10 – Section BB. The display of works, punctiliously laid out against the dazzling whiteness of the space, feels minimal, and the works together emit a frugal, almost Arte Povera vibe. The exhibition, curated by Andrae and Louise Haselton, is straightforward: four Adelaide artists from these two generations. Bronia Iwanczak and Linda Marie Walker are well-established (their careers taking off at the same time as Andrae’s), and Izabella Shaw and Meng Zhang are recent art school graduates. There are no immediate or obvious pairings, and the show’s title suggests nothing in the way of a narrative or theme. So it is up to the visitor to take each work as it stands.

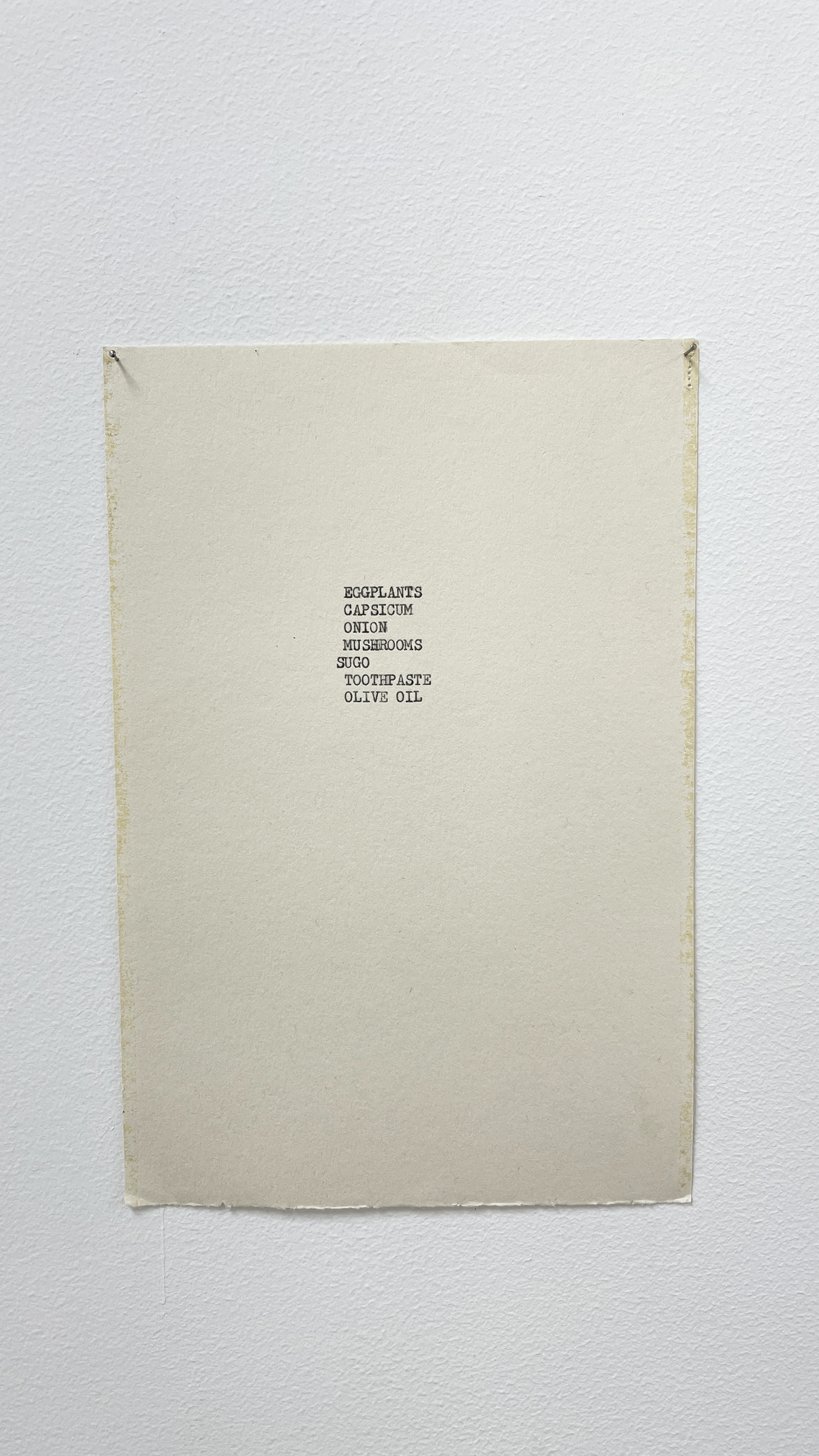

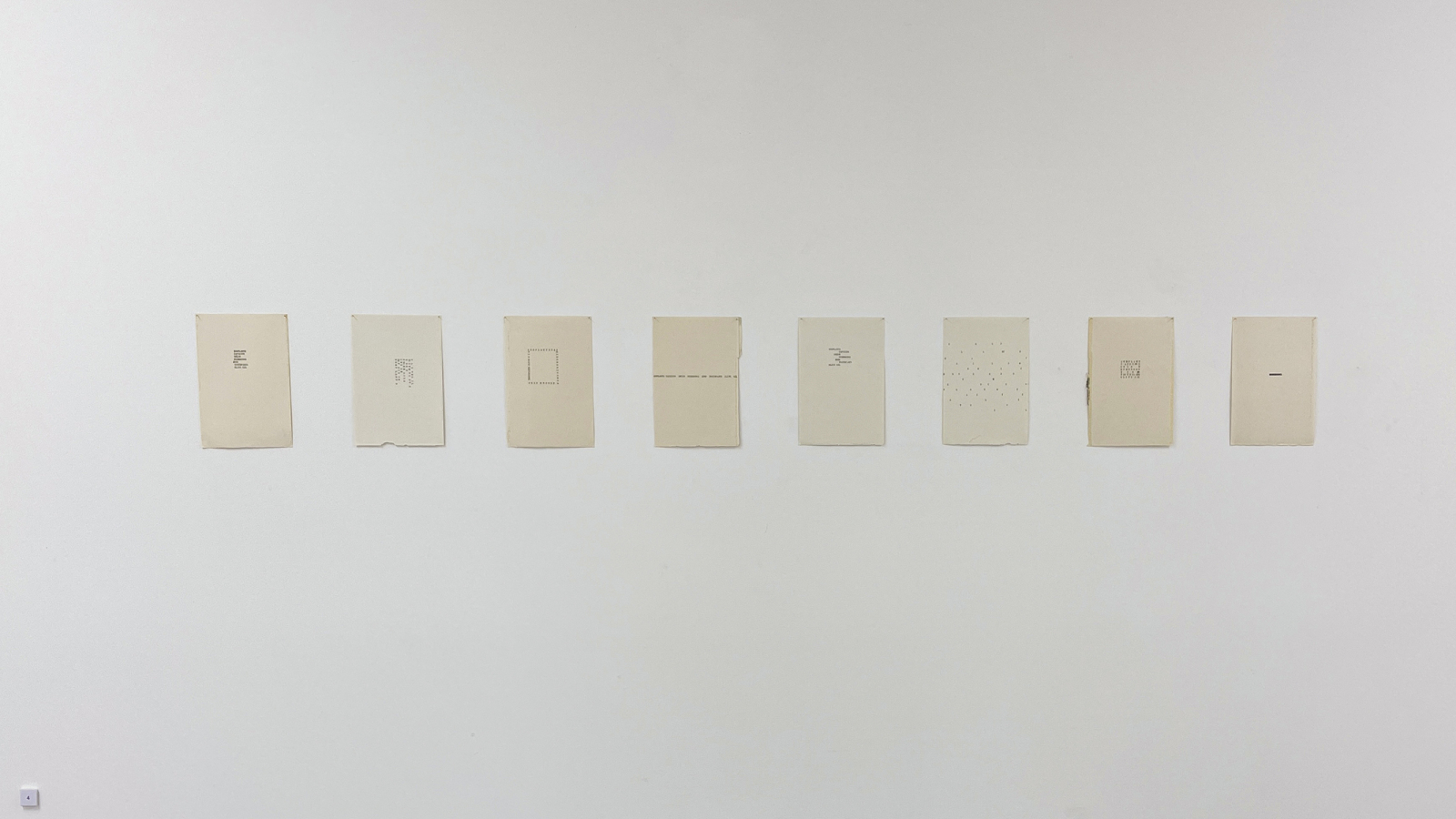

Shaw shows a series of sculptural objects and text-based works. The objects draw most attention. Two mops lean into a corner of the gallery in a sort of symmetry, mimicking or mirroring one other. The threads of the two mop heads intermingle with each other, tendril-like. I imagine each dragging the other across the floor, like a poltergeist. Or one can imagine holding both shafts, one in each hand, as a kind of cleaner cum cross-country skier. In the centre of the space two straight ladders lean into each other. Their top rungs interlinked to make another uncanny, impractical object. These two works, Codependence #1 and #2, are not just the practical joke they appear to be; as their title suggest they embody an unhealthy unbalanced relationship. One more work of Shaw is eight A5 pages of typed text mounted on the wall. A Conceptualist shopping lists: Eggplants, Capsicum, Onion, Mushrooms, Sugo, Toothpaste, Olive Oil. The seven items repeat, arranged in different ways, looping around the circumference of one page, overlapping in a cacophony of ink.

Iwanczak’s Defence Rhythm, a work from 2001, consists of small, lines and ouroboros-like circles of half eggshells nested one into another. Some are spray-painted silver, others au naturel. They lie scattered on the floor, ’90s style, without benefit of pedestal or floor guard. I imagine somebody wolfing down eight eggs a la coque at a hotel buffet and neatly fitting the empties into each other. They also suggest empty husks from some hatching creature, or fossilised parasites crawling on the floor.

Walker, known as pioneer of postmodern art practice in ’80s Adelaide, and in the ’90s and 2000s as a curator and writer, presents surprisingly modest textile and ceramic works. Three small rectangles of embroidery, Cloths For Nothing, are fixed to a wall, loose geometric patterns stitched on and through three layers of colourful fabric scraps. Knowing Walker’s practice as a phenomenologically-informed writer, it is hard not to see the stitching also as a kind of abstract writing or script, a legible trace of motion of body and mind. Two more of these textiles, Cloths for Wonky Pots, are placed on simply constructed low wooden tables. Atop them sit glazed clay pots, their asymmetries another trace of human care, attention or fallibility. These textiles and objects slow visual awareness to their own speed, drawing thoughts and feelings into a correspondingly slow, careful rhythm.

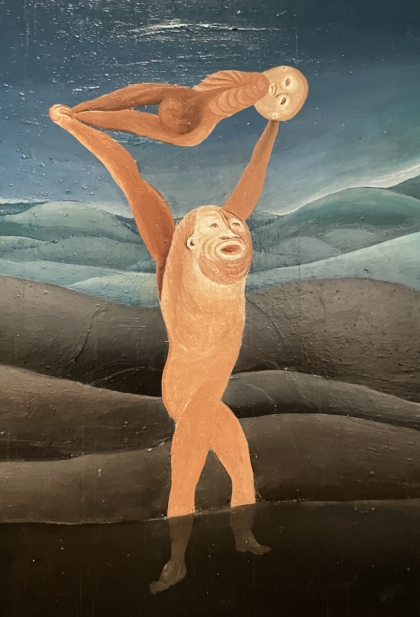

Zhang presents a series of large unframed prints of digital photos. These show small, cast objects, painted in monochrome, and blown up to a large, almost monumental scale. Most striking is a chipped plaster fist, resting on its knuckles, and painted faint red. Enlarged, it acquires something of the scale, presence and power of the Belvedere Torso. In the context of the other artists’ subtle and gentle works, Zhang finishes off the show with an affecting flair – and a powerful punch.

No Comments