Submitted Review

‘Both brothers’ oeuvres come across as explorations of psychogeography.’

‘Dušan and Voitre Marek: Surrealists at Sea’

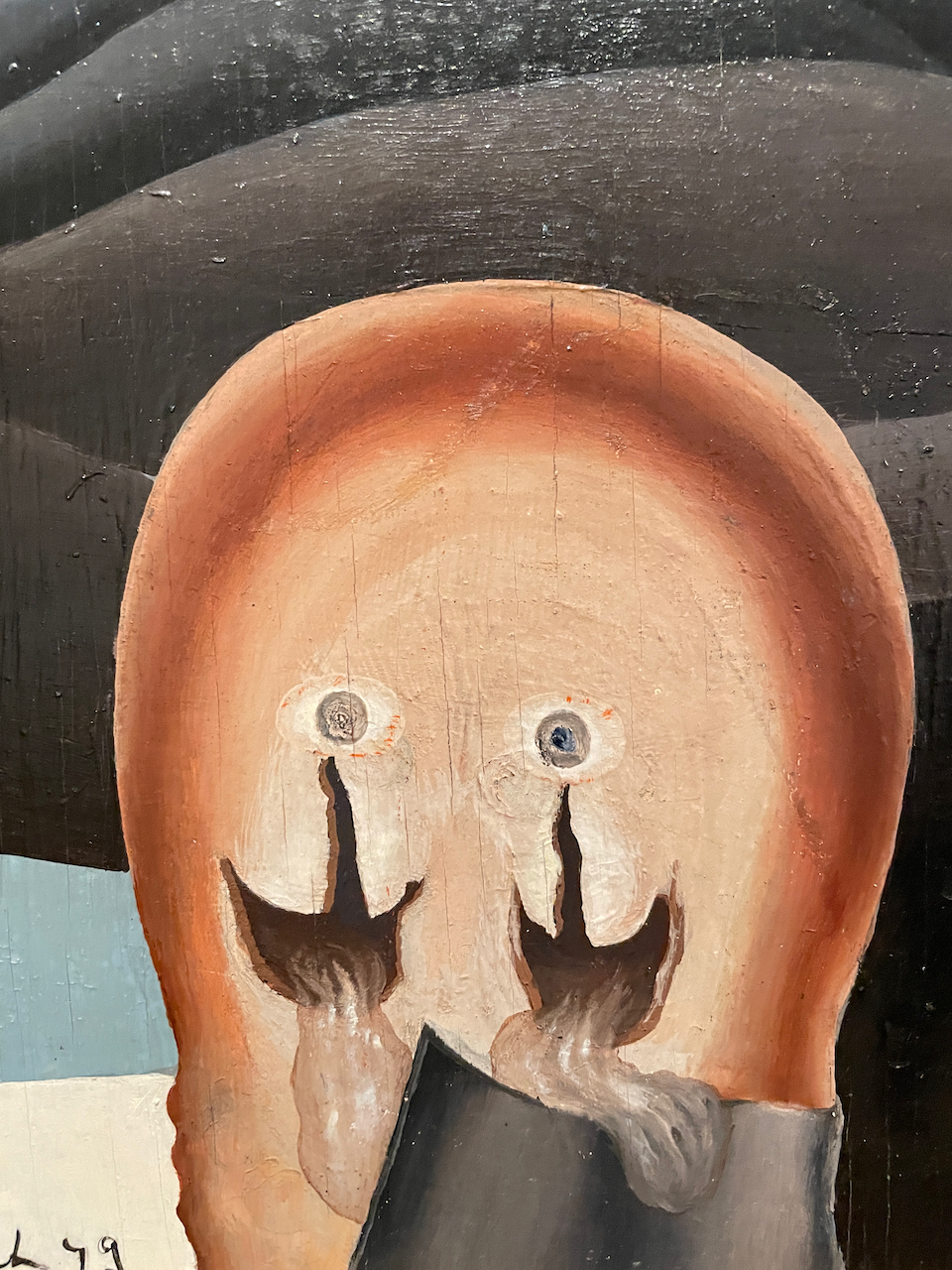

The Art Gallery of South Australia has opened an impressive exhibition of the works by two artists, brothers, Dušan and Voitre Marek. They came to Australia at the end of the forties, escaping the political upheaval in their native Czechoslovakia. The initial plan to make for Canada or France was abandoned when they were offered a visa to Australia whilst in Germany. This is where the exhibition starts, with paintings made aboard the SS Charlton Sovereign. From there the exhibition presents thematically clustered work from their varied oeuvres. As the title of the exhibition suggests, the brothers were at their most Surrealist on, and around, their long voyage to Australia. It is these fever-dream paintings that most clearly reverberate with the themes and techniques of European Surrealism. They combine something of the frantic hallucinatory quality of Dalí’s 1930s paintings or the work by their compatriot Toyen. Their styles, at this point, were so similar, that one might need to rely on the wall labels to distinguish their works. But as they settled into life in Australia, their distinctive sensibilities, styles, and motifs come to the fore. Voitre would eventually come to develop a finely-tuned Expressionist style, which he turned towards religious and spiritual subjects in church commissions. Dušan came to embrace Modernist abstraction, exploring gestural techniques, and organic forms. Yet throughout their careers, both retained the questing, urgent energy of that early surrealist vision.

In the first room of the exhibition, we encounter various works made during their voyage. Dušan and Voitre recorded aspects of their crossing in notebooks, and quotes from these appear on the walls. Art materials were difficult to come by on board, so they made do using shipping crates and packaging as panels. In Dušan’s small painting, Gibraltar (1948), abstract geometric shapes coalesce into a mixture of land and sea around two pale-skinned mannequin-like female figures: one upside down, headless, nude, and triple-armed, the other, right way up, wearing a narrow, high-waisted loincloth, and lowering her white brassiere. They are like displaced reflections of one another in the watery landscape, together recalling figures on a playing card but also the deadpan advertising-poster style of Magritte. The painting hangs in an aperture in a purpose-designed, freestanding wall so we can observe both sides. For on its reverse, Dušan painted another work, Program (1949). This is an equally weird image, made almost a year later in Adelaide, and showing a hallucinogenic rendition of a landscape that must have appeared unutterably foreign to the painter.

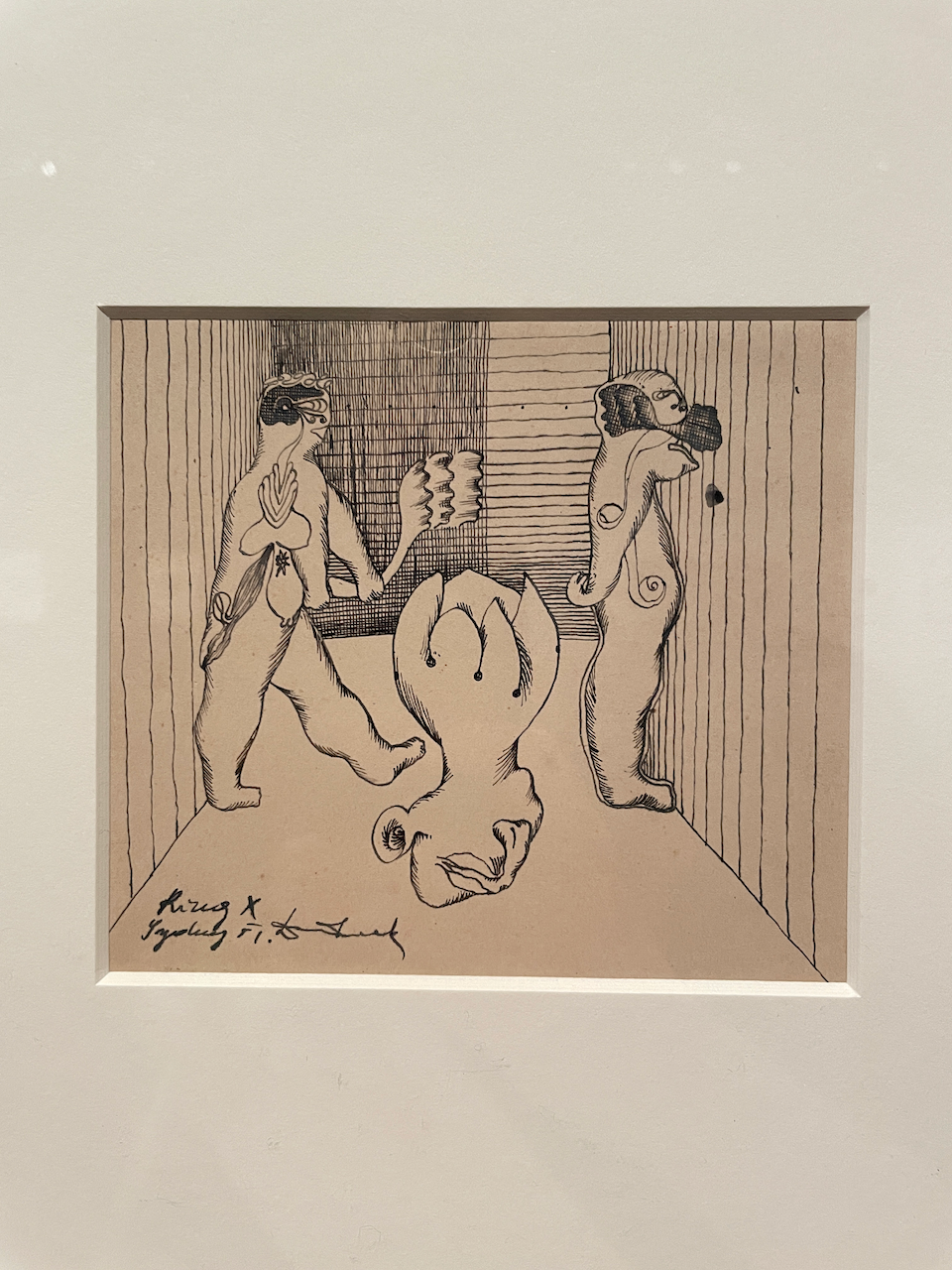

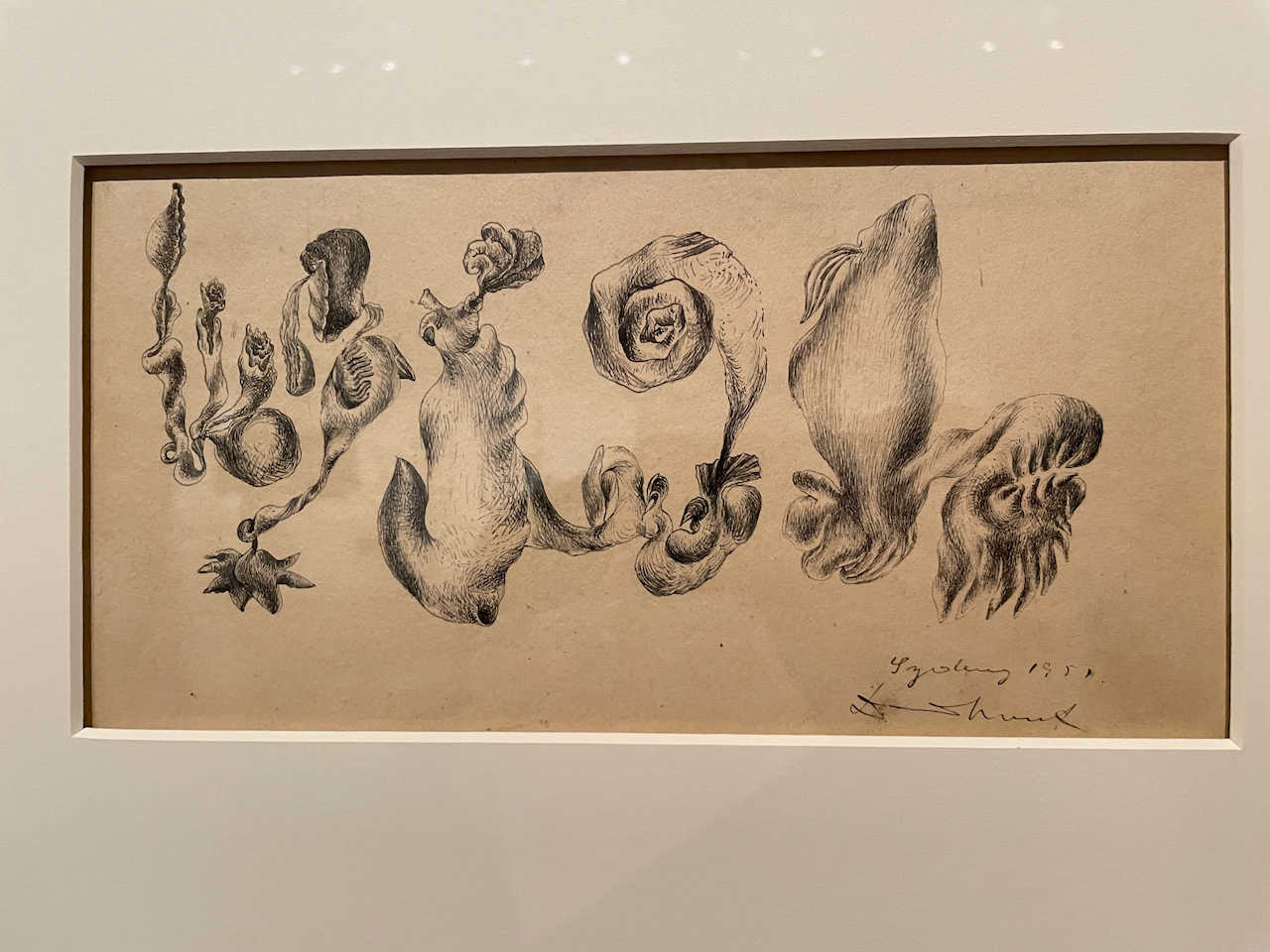

In the next room we find fantastic pen and ink drawings, some from before the start of their journey, some scribbled in later notebooks. Dušan’s various “biomorphic forms”, grotesque haunted Hans Arp-like bodies, have a clarity of line and determinacy akin to the dream-drawings of De Chirico. Some works in the exhibition are presented on mirror-covered walls. In the case of Gravitation – The Return of Christ (1949), itself containing a convex mirror as the bulging sail of a ship, this style of presentation makes the work seem afloat or adrift in the space. Apt as it reinforces the dark seascape in which tormented humanoid figures appear on the foreshore, seemingly ejected from the small vessel on the horizon.

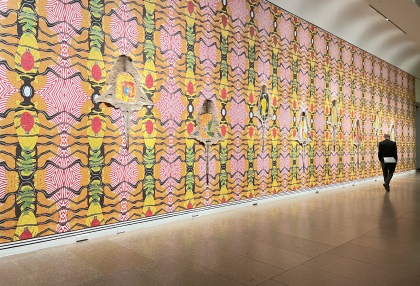

From there, the brothers’ careers take various twists and turns. In the 1950s, Voitre, turning his hand increasingly to sculpture, spends time as a lighthouse keeper, producing photographs of a sculpture bust of his young daughter, Olga, placed on the wind-blasted shore of Kangaroo island as if washed up in a storm. Meanwhile, Dušan makes a career as a jeweller, his finely wrought mid-century modernist bracelets, brooches, and even an ashtray giving the Adelaide bourgeoisie a bracing alternative to their usual diet of kitsch. Dušan also turned his focus to film, making animations using a range of techniques and a feature-length movie playing in the final room of the exhibition. The flashing colours and quivering shapes of Adam and Eve (1962) – psychedelia before its time – playfully retell the biblical story in cutout stop-motion animation. Dušan’s hand – the hand of the creator, so to speak – even makes an appearance. The exhibition then turns to Voitre’s religious sculptures, and Dušan’s voyages into abstraction – only superficially does this imply the brothers’ oeuvres moving apart as they remain connected by an interest in the ethereal and transcendental. Voitre’s fine sculptures grace many Adelaide churches of the 1960s. These are existentialist, expressionist sculptures that imagine traumatised human bodies as attenuated filigrees of form. By contrast, Dušan’s 1960s abstractions turn to examining human-scale gestures and chemical interactions between materials. Blurred backgrounds of rich colour are host to blots and squirts of paint. Summer in Coorong (1963) suggests something of the hot, hazy atmosphere of the place in a red and white blur, but it also plays host to curls of red and yellow paint squeezed directly from the tube, like tomato sauce and mustard.

So, these “Surrealists at sea”, were they Surrealists on land too? Stylistically speaking, no. Their later work has little of the recognisable stylistic elements we associate with surrealism. But beneath the constant explorations of style and media, there is continuity in their work. Both brothers’ oeuvres come across as explorations of psychogeography. For Voitre, that psychogeography enters spiritual territory. For Dušan the unconscious is partly liberated from the figurative, to run its course in a world of abstract, cosmic space. For them both, the energy, bubbling intensity and the creative fertility of the unconscious remained a guiding principle – a lodestar. It guided them on their journey south, and it guided them just as truly on the long, winding and diverse paths they took in Australia.

No Comments