Submitted Review

Margel Hinder: ‘Modern in Motion’

‘pray! a concrete-poet’s riposte.’

Hinder Rising. Streeton Setting

Out of the sun-splashed and into the dark,

Solar-system spin of kinetic art.

Streeton’s Purple Noon fading fast, arise Margel Hinder’s

Modern in Motion – pray! a concrete-poet’s riposte.

A ‘palette’ cleanser, a chaser,

a spell from blue and gold. My friend The Chair was not.

But I was sold.

Hinder is civic, urbane, chic. Sharp, cool, clean.

Didactic. Nearly homochromatic. And a bit neglected.

Born in Brooklyn, raised in Buffalo, trained in Boston,

migrated south via the sacred-modern site of Taos, New Mexico.

Down-under, but not, despite the dearth, undone:

Still young at 28 in ’34 when the Hinders made Sydney home.

A rhyming couplet, Margel and Frank Hinder have shared 3 surveys.

This is her 1st solo retrospective. 3 rooms of her own.

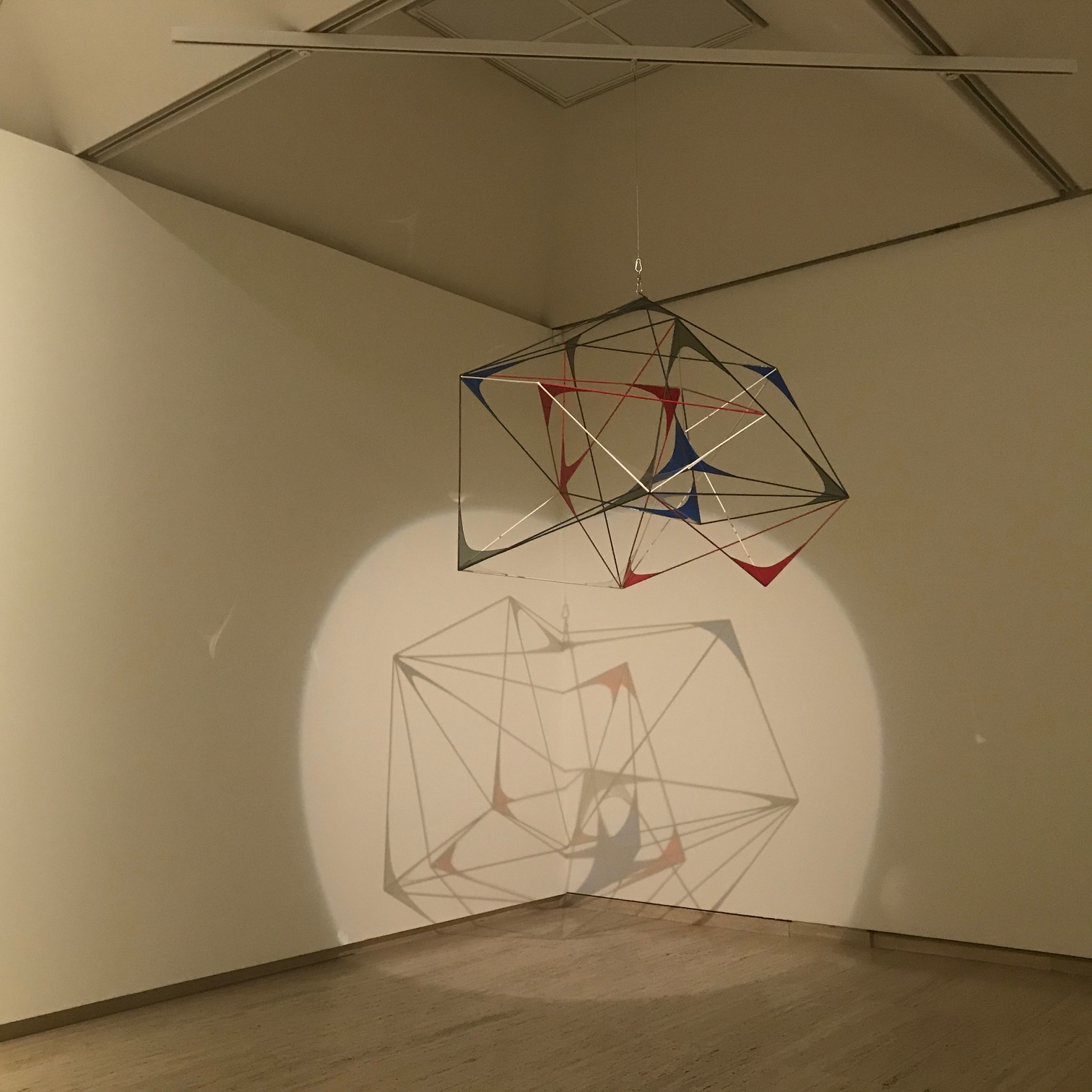

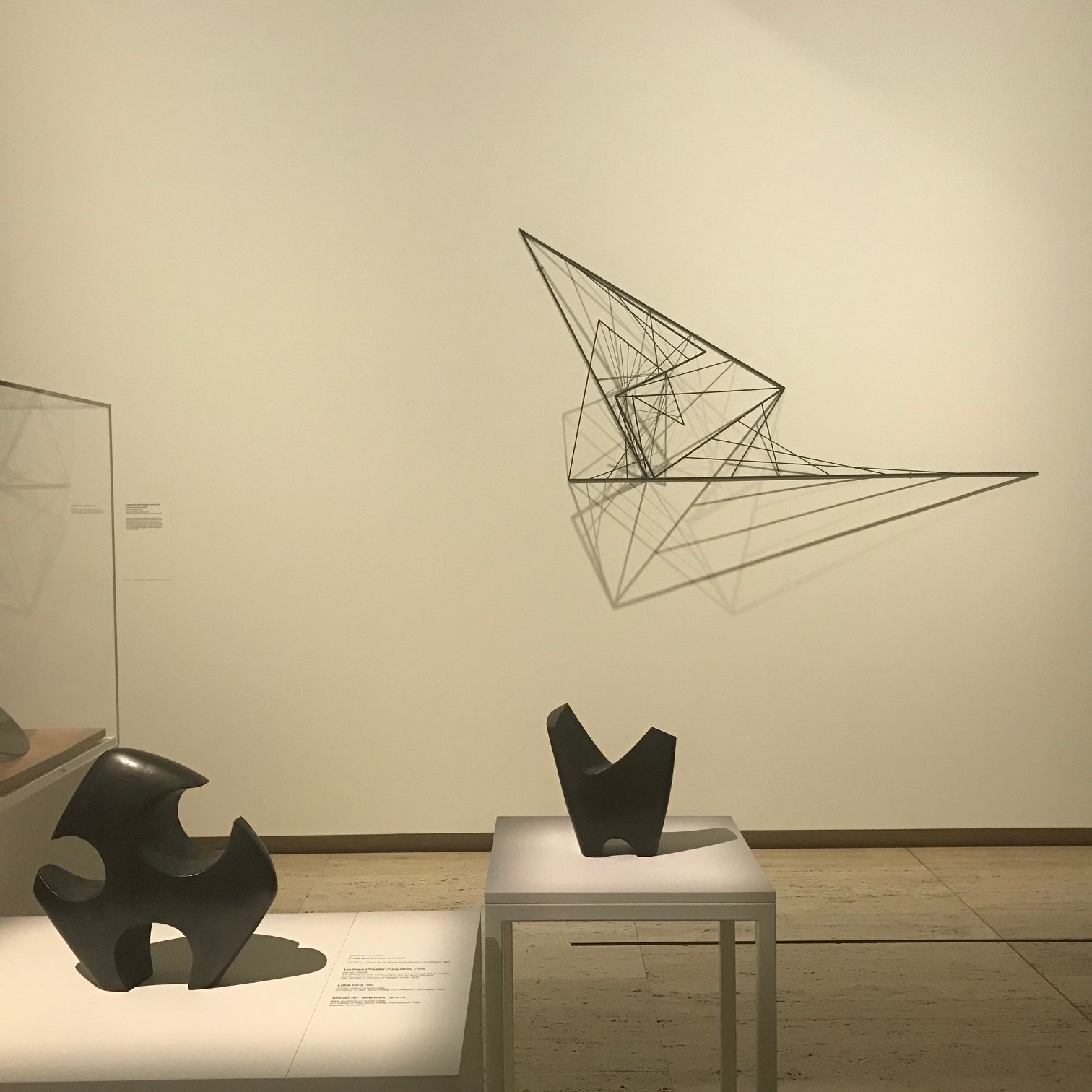

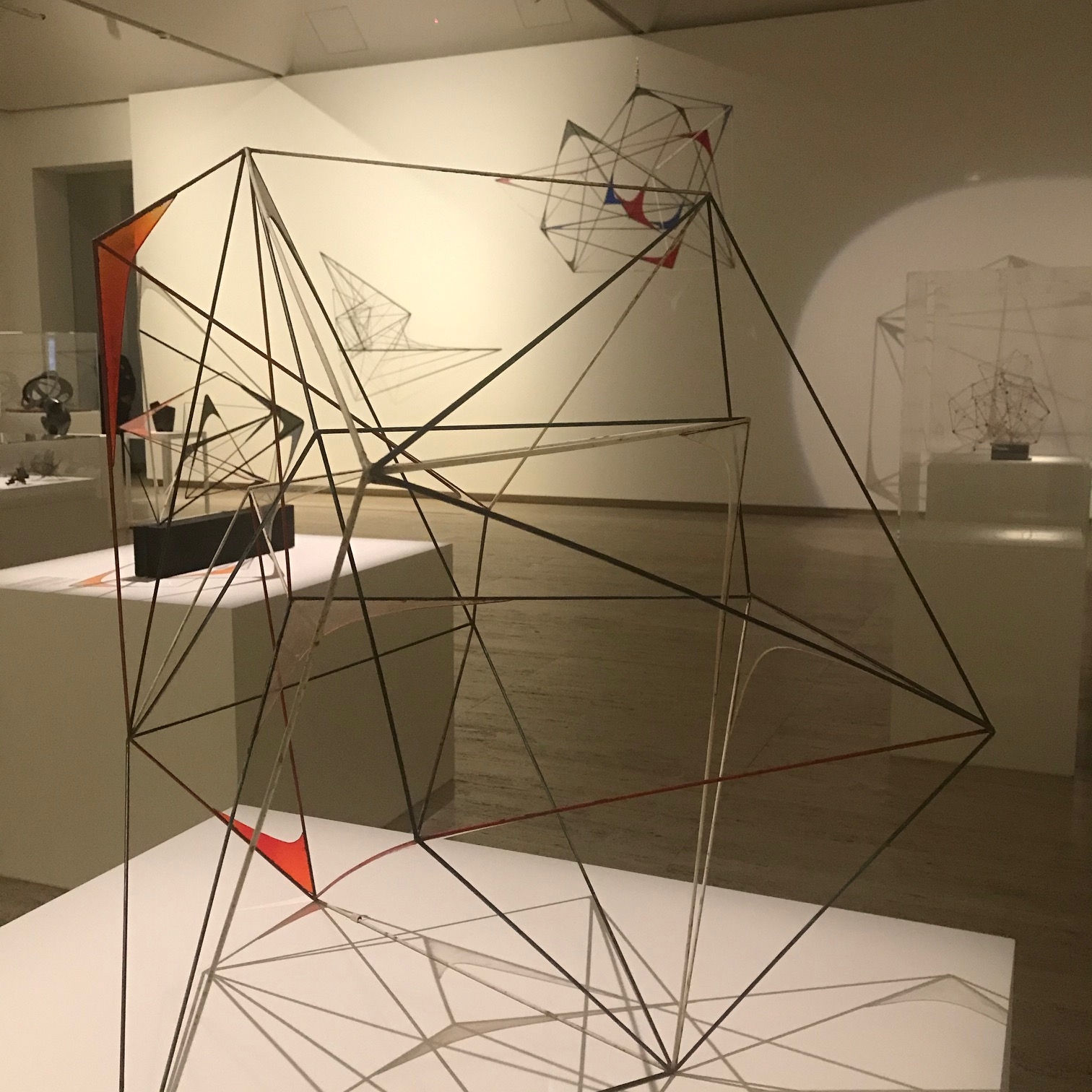

A dark antechamber of spare, suspended, spot-lit wire sculptures,

revolving 50s-décor-style. Movement, space, material, shadow:

dynamic symmetry in all its graces.

The central room floodlit convention, white plinths for agile carvings, bending tradition, aligning with the new. ‘Well-known abstract sculptress’ emerges from stone and camphor-laurel, catching Perspex on the fly. A cornucopia of maquettes, lost loves and never-beens: treasures for the eye. A fan of technological advance and metaphysics, she was in sync with international abstraction and the avant-garde.

Wed to constructivist methods and situated firmly in the 20th C, her transit was more facture than faction.

Leaving her ‘lovely wiry things’ of ‘luminosity and light and space’ in the ‘60s for ‘great big heavy sculptures’ sounds like the biological biography of woman. But Hinder’s is a middle-age of triumph, a refusal to be handicapped by the feminine, or hijacked by feminism.

Her principal cause was making the work ‘work’. This meant scaling municipal contours and managing corporate conflicts. Nowhere was her mettle more tested than in her monumental outdoor commissions, some still extant.

Modern in Motion presents fine immersive VR renderings of two, including her elemental fountain-masterpiece in Newcastle’s Civic Park, completed when she was 60 in ’66. But the story didn’t end there. In 1970, the formalist ‘pile of junk’ to quote the local press was renamed The Captain Cook Memorial Fountain, capitalising on public-works funding for Cook’s-landing-bicentenary-nation-discovery-monuments. This seemed to smooth the civic reception of the fountain back in the ‘70s. Not surprisingly, the naming plaques were discreetly removed in decolonising protest when the Cook 250th sailed around in 2020. More surprising is that the Hinder retrospective makes no detour to Newcastle Art Gallery, despite its Brutalist sentry position above the fountain. It’s the old story of gravitational force, for regional centres too close to ‘the centre.’ Hinder’s next stop is Heide. Freight hurts.

No Comments