Submitted Review

‘And what might we yet become?’

Jess Johnson, Simon Ward ‘Terminus’

In Jess Johnson and Simon Ward’s Terminus, the call is coming, at once, from both inside and outside the house. Technological intervention into human experience of the world is both a formal and a philosophical problem thought through, if never resolved, by the work; this is what makes the show more than simply a bedazzlement of Johnson’s drawings by Ward’s animation.

VR raises questions about the boundaries of the human in our contemporary technocracy: how much do we control our participation and place in cycles of production and consumption? The program notes at the Maitland Regional Art Gallery describe Johnson and Ward’s work as a choose-your-own-adventure. They even suggest that the audience could understand their journey through the VR-world as a hero narrative: we face challenges and emerge with new knowledge to share at the end. Indeed, I think we do emerge with new knowledge. Only, this is knowledge precisely of our inability to choose our own adventure when technological processes take up their own agency.

We are led through five interwoven VR realms in the show, each feeling more like a dystopian Super Mario track, a button stuck down on the controller. A viewer can, of course, turn their head to trace different horizons of the world they newly inhabit, but control over the viewer’s movement, or other interactivity functions, is limited. A sense of estrangement from our own embodiment is then both an effect of the medium and its manipulation, as well as the ‘subject matter’ we are made to encounter by it.

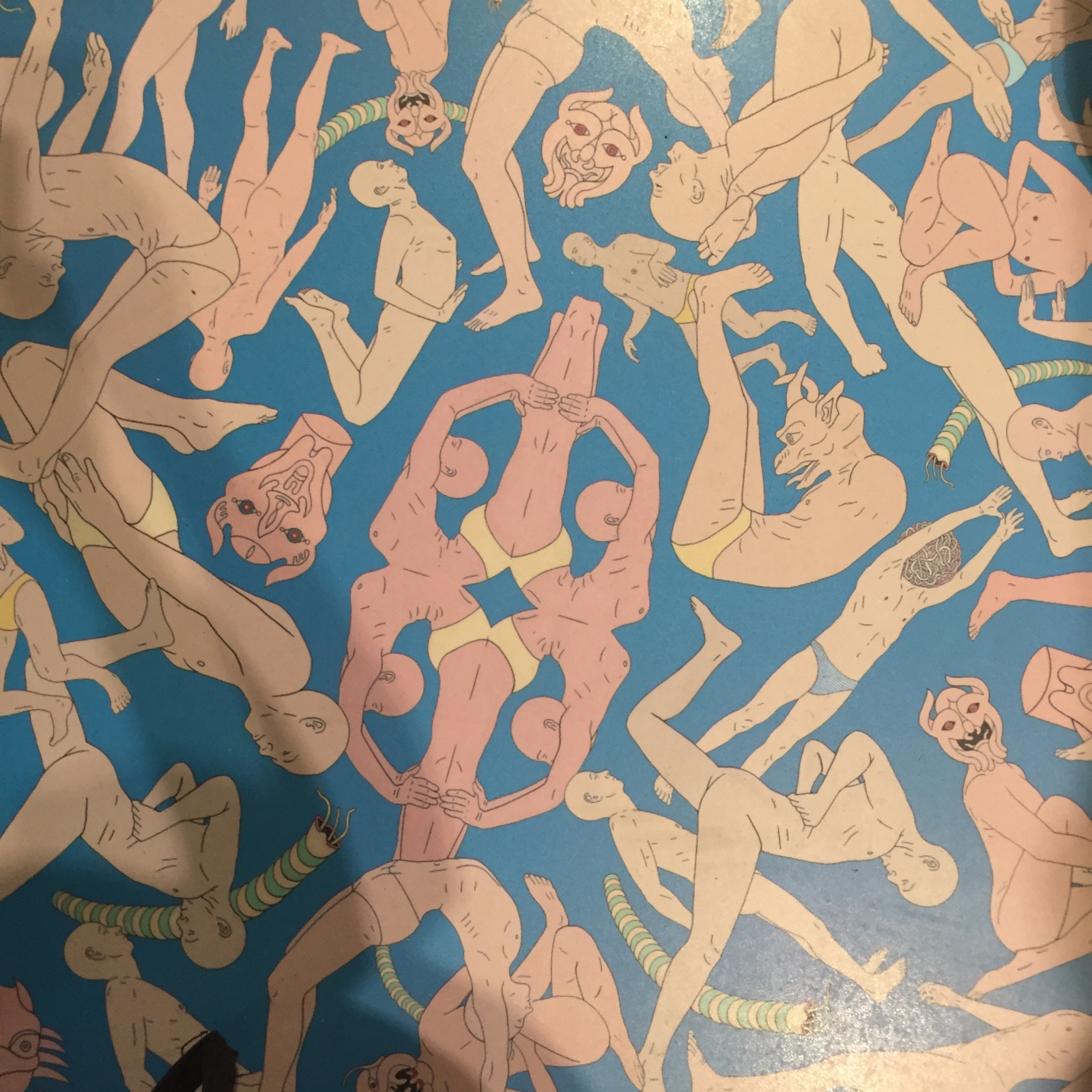

Unable to walk away, we are ourselves subject to the scenes of human subjection that the work depicts. Mannequin-like figures, abjectly approximating the human in the weird manner of porcelain dolls, are made to support the structures of buildings, lift objects rhythmically, incessantly. Eventually, they are tumbled off an edge into negative space. In this last scene, the body becomes most clearly another form of capital, churned through a digitised system of construction/production and utilised to support whatever kind of state we find ourselves within.

This is the call coming from outside the house: we are funnelled into awareness of the intrusion of technological production systems (of reality, of data, of consumer goods, and even of the flesh) into ‘human’ territory.

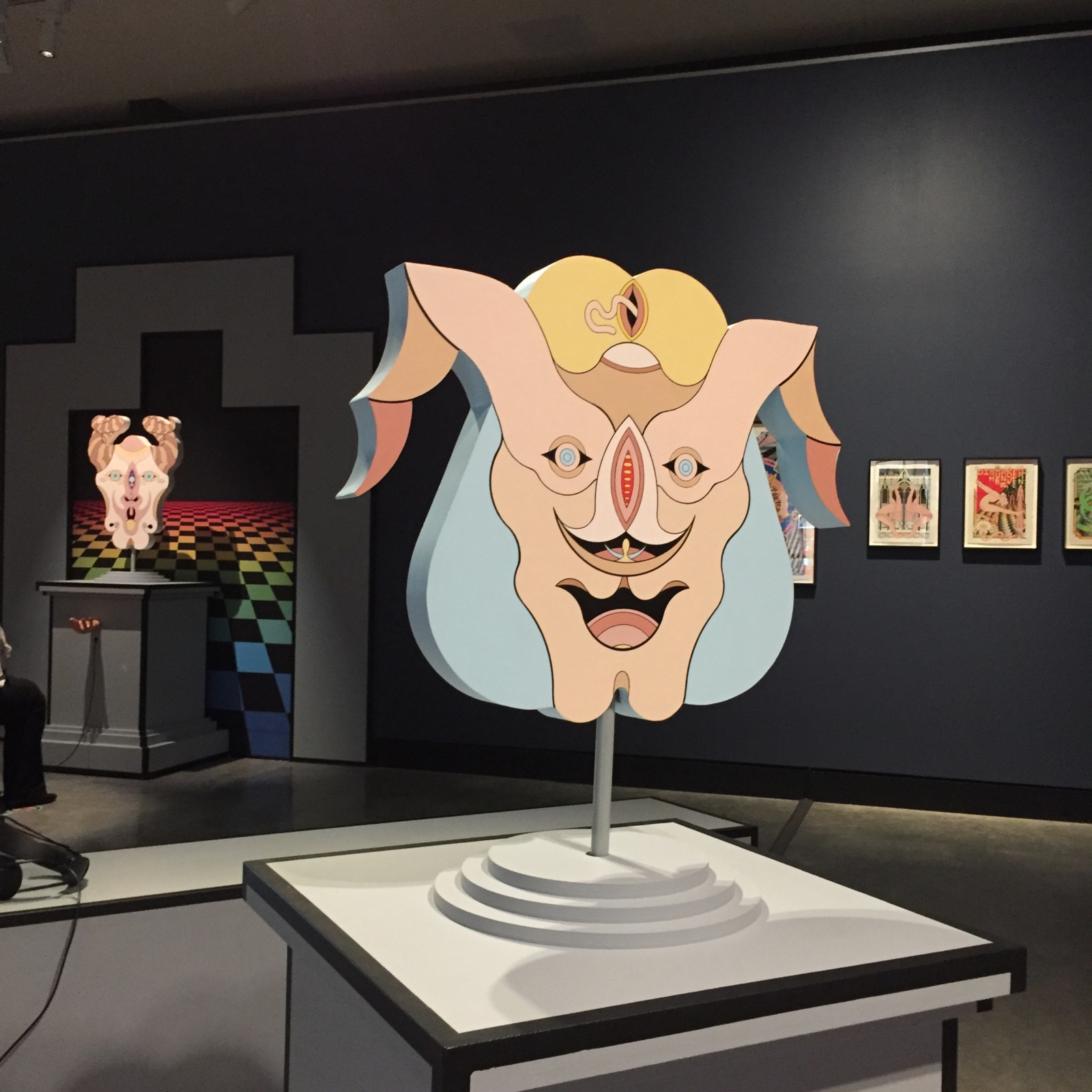

But there is still the call coming from within. Many of Johnson’s drawings feel hyper-genital — both entrancing and repulsive. Faces, or perhaps masks, which flicker towards and away from the human as we take them in, seem to be set across hips, or between splayed legs. A moving figure, simultaneously botanical and phallic, recurs throughout the five works; we eventually find ourselves falling through its centre, in the fifth. The imagery of the occult, which permeates this virtual reality, similarly calls upon the dangerous, the destructive, or the uncouthly desiring. It stakes a claim for the location of these difficult impulses at the heart of the human psyche. Flashes of recognition, or of identification, here, are alarming. What, exactly, are we? And what might we yet become?

If we are to hold that technological intervention into the human is the source of the scariness in Johnson and Ward’s world, a question remains: who built the technology? Who developed the VR? One work shows us a columned temple, with text across the facade: ‘the rats who build the labyrinth from which they plan to escape.’ Perhaps, here, we escape from one labyrinth, into another. Escaping from the ‘real,’ at least in this setting, is as easy as putting on a headset. How easy is it, we’re led to wonder, to escape from the virtual — especially when the virtual has become us?

No Comments