Submitted Review

‘Hayes’ paintings speak of human frailty and insecurity’

The.LongBoard: Elizabeth Burns Coleman 'Cameron Hayes at Australian Galleries'

When I meet Cameron Hayes at the gallery to discuss his work, he emphasizes that he is not looking for an aesthetic criticism, but for someone to discuss the ideas he is exploring within the paintings. This suits me, as a philosopher rather than as an art critic, and also because of the narrative structure of the work. Hayes’ paintings are meditations on a series of themes of humans caught in a structure beyond their control. Hayes’ paintings have been described as an exploration of “cultural power structures and contemporary political issues,” yet what I see is a profound ethical vision, and an existential absurdity. To me, Hayes’ paintings speak of human frailty and insecurity, the struggles for status and identity, hypocrisy, and hope. While these themes are evident in many of the paintings, I restrict my discussion to his latest painting, She died in the child welfare tribunal, he died in an adult bookshop, after which the exhibition is named.

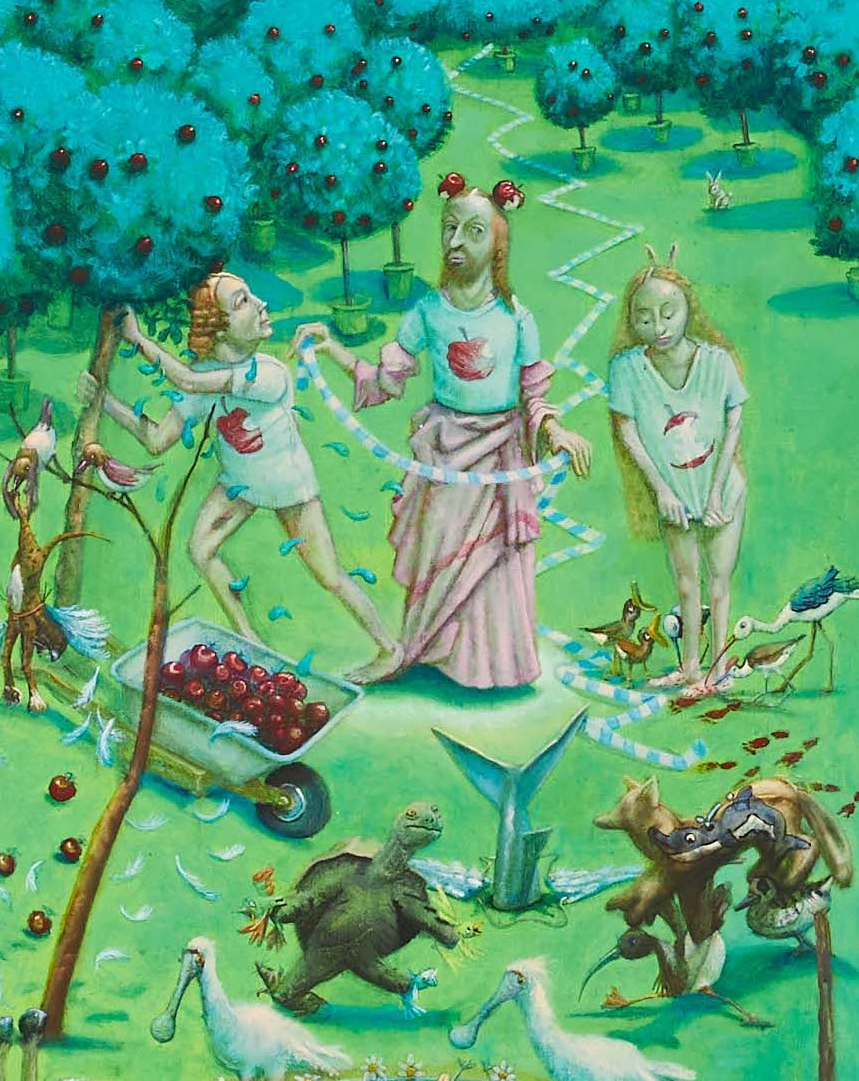

She died in the child welfare tribunal, he died in an adult bookshop is structured as a triptych after Hieronymus Bosch’s (1503-4) The Garden of Earthly Delights. A Creative panel, Reality panel, and Consequence panel provide the structure of a moral narrative. However, in this image, the moral message concerns the brutality of the “delight” in public shaming. Hayes’ Creative panel is a story of the creation of blame. God creates Adam, who is given the task of naming the animals, creating a structure in which animals are categorized in relation to his (Adam’s) interests and needs, and in giving Adam free will, God is not responsible for his actions. When Adam and Eve eat of the tree of knowledge, they gain the knowledge to name and judge others. The Reality panel is structured in a series of scenes in a rhythmic loop. He (Adam) dies in an adult bookshop, and she (Eve) dies in the child welfare tribunal. They are branded as certain kinds of people at the moment of their death. The towers of Twitter, Google, and Facebook record their lives at their worst moment, creating their identities for others in the process of naming and shaming them. The centre of the frame represents a moral universe of the quick, easy judgment and online pile on, with a scene from a cemetery where a tourist bus has stopped to allow people to listen to an obituary. The statues in the cemetery are of comic book figures “signalling their virtue with kicks and punches.”[1] Shaming is not a new phenomenon. In the detail of the painting, a parade of the shamed is found in the branding of “horizontal collaborators,” the French women who had relationships with German soldiers during WWII, and children as delinquents.

There is truth in this painting. Hayes’ emphasis on social media and the online context in which this occurs is important. Emily Laidlaw notes, “The ramifications of shame sanctions are magnified when executed online, because the punishment can be disproportionate to the social transgression, the perpetrators anonymous and diffuse, and the reach of the shaming immediate, worldwide and memorialized in Google search results.”[2] The journalist Jon Ronson has explored the consequences for those who have been shamed, and the trauma. Monika Lewinski, one of the most shamed individuals of the late twentieth century for her affair with US President Bill Clinton comments, “I felt like every layer of my skin and my identity were ripped off of me… “It’s a skinning of sorts. You feel incredibly raw and frightened. But I also feel like the shame sticks to you like tar.”[3] A poorly phrased joke, such as that expressed on Twitter by Justine Sacco,[4] or even overheard, such as that posted by Adriana Richards when she overheard and posted a joke between colleagues at a conference,[5] may lead to the loss of a job, social isolation and ongoing anxiety. The shaming of games designer Zoe Quinn with false accusations that she slept with a journalist for a favourable review of one of her games led to death threats for her supposed misdemeanour.[6] In Hayes’ painting those who are shamed must leave their relationships and lives, and the suburbs are full of removalist vans.

One imagines that Hayes might know something about shame. He describes himself as the “son of a career criminal and pathological liar.”[7] His family often suffered eviction and the repossession of family goods. His father, who had many aliases, discouraged him from giving his real name to strangers, and he lived with a sense of insecurity, the fear eviction and repossession. Growing up in such an environment could not have been easy. Shame bleeds, just as pride bleeds. We may be proud and reflect ourselves in the achievements of our parents or children, but equally we share shame. School, and school yard taunts could not have been easy. Hayes is not quick to judge. If anything, he seeks an understanding that allows him to see his father’s transgressions in context; and not to allow his father’s failures to determine the value of his (his father’s) life. There was more to him.

The painting might be interpreted through the lens of Jean-Paul Sartre’s line, “hell is other people.”[8] This quote from No Exit is spoken in a scene where three people arrive in hell, which turns out to be a parlour. There is no fire or brimstone, only the other people in the room. The punishment is the shame produced by the judgment of others. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre develops this idea in terms of a realization of how others come to see us.[9] He describes a scene in which a person is looking through a keyhole. At first the person experiences the joy of viewing others as objects, subject to their judgement, but upon being seen by others with their eye to the door, realizes that they are seen, and judged, as a Peeping Tom. This creates the sense of self as an object and the sense of shame. Not only do we objectify the Other, the Other has the power to objectify us, to freeze us into a kind of being, as a Peeping Tom, as someone who looks at pornography, or as someone who fails to care for their children. The only defence is to objectify others through shaming. In Hayes’ painting, the consequence of this defence is seen in the final, Consequence panel. In this panel, shaming is so essential there is little need for any substance to the accusation, masks that distort people’s identities are put on the corpses of people on the gallows. Human relationships are undermined, children are brought up to throw stones.

Failing to meet social expectations may be sufficient reason to shame someone. Shaming is “a form of social control,” as Eric Posner suggests, “[i]t occurs when a person violates the norms of the community, and other people respond by publicly criticizing, avoiding, or ostracizing him.” [10] The reason may be trivial. In one scene in the painting, Lindy Chamberlain, who was wrongfully accused of killing her baby, leads a procession of elderly robots which have outlived their purpose. It was not Chamberlain who should feel shame, but those who wrongfully attacked her. Yet, at the time, it was widely believed Chamberlain had to have been guilty because she did not cry in court,[11] just as the character Meursault in Albert Camus’ novel The Outsider is seen as a monster for failing to weep at his mother’s funeral. Camus summarised the novel with the line, “In our society, any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.”[12] The inclusion of Chamberlain introduces an absurdist note, the sense that the individual is a participant in a world that they cannot quite comprehend, where the smallest action or reaction may send life in a totally new direction. According to Hayes, the shamed person is defined and, as it were, brought into existence through the process of shaming, “The shamed person doesn’t just wander through our life and live on without us, they are trapped and marked in that time of intersection.”[13] They are branded. It is the absurdity of a world of reality television, where a person may be shamed because of the edits of a director, [14] and of the construction of media images that construct the roles people are expected to play. Twenty years later, Chamberlain still lives with the taunts of strangers: dingo howls are called outside her house.

Hayes’ painting suggests that we do not understand the people we judge to be immoral. In fact, we require distance and even a degree of ignorance. This point is emphasized by the police tape that separates Adam and Eve from the animals in the Creative panel and in the Reality panel, where it separates the jeering crowd from the accused. “[K]nowing someone too well only creates confusion, empathy and mitigation and so – much too little certainty.”[15]

As in Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, what emerges from She died in the child welfare tribunal, he died in an adult bookshop is a moral lesson. It is a warning about the delights of shaming, and the epistemic uncertainty within which we make moral judgements. We cannot know “the truth” or sum up a person in terms of a moment of their lives. To do so is to perpetuate a profound injustice.

EBC

Elizabeth Burns Coleman

Dr Elizabeth Burns Coleman was awarded two postdoctoral fellowships, one from the ANU’s centre for Cross Cultural Research, and one at Monash across the Communications and Philosophy sections. She has taught legal philosophy, political philosophy, ethics, and philosophy of art at Australian National University, La Trobe University, Wollongong University, and Monash University, where she currently teaches Media and Culture, and Communication Ethics, Policy and Law.

Footnotes:

[1] Cameron Hayes, exhibition notes, She died in the child welfare tribunal, he died in an adult bookshop, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 13 April-2May, 2021.

[2] Emily B. Laidlaw, “Online shaming and the right to privacy,” Laws 6, no. 3 2017, p. 3.

[3] Jon Ronson, “Monika Lewinski: The shame sticks to you like tar”, The Guardian, April 22, 2016,https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/16/monica-lewinsky-shame-sticks-like-tar-jon-ronson

[4] Jon Ronson, So you’ve been publicly shamed, Riverhead Books, 2016.

[5] Laura Hudson, “Why you should think twice before shaming anyone on social media,”, Wired, July 24, 2013 https://www.wired.com/2013/07/ap-argshaming/

[6] Keith Stuart “Zoe Quinn: ‘All Gamergate has done is ruined people’s lives’”, The Guardian, December 4, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/dec/03/zoe-quinn-gamergate-interview

[7] Cameron Hayes, personal communication, April 10, 2021.

[8] Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. No exit and three other plays. Vintage, 2015.

[9] Jean Paul Sartre. Being and nothingness: An essay in phenomenological ontology. Citadel Press, 2001.

[10] Eric Posner, “A terrible shame: Enforcing moral norms without law is no way to a virtuous society,” Slate, April 9, 2015, cited in Laidlaw, “Online shaming,” p. 2.

[11] Tarla Lambert, “‘Why didn’t she cry?’ How Lindy Chamberlain became the poster child of life shattering gender bias,” Women’s Agenda, August 17, 2020, https://womensagenda.com.au/latest/why-didnt-she-cry-how-lindy-chamberlain-became-the-poster-child-for-life-shattering-gender-bias/

[12] David Carroll, Albert Camus the Algerian: Colonialism, terrorism, justice, Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 27.

[13] Hayes, exhibition notes.

[14] Kate Demolder, “Humiliation TV: Has reality TV’s shame culture led to rise of trolling,” Independent.ie, February 28, 2021. https://www.independent.ie/life/humiliation-tv-has-reality-tvs-shame-culture-led-to-rise-of-trolling-40122018.html

[15] Hayes, exhibition notes

Disclaimer: This exhibition was curated by Marielle Soni, a board member of The ReviewBoard.

The author was invited by the artist to respond to his most recent work. The author has no affiliations with the gallery, artist or curator beyond the invitation to view, reflect and respond.

No Comments