Submitted Review

The.LongBoard: Briony Downes on Thomas Griffiths Wainewright 'Paradise Lost'

Paradise Lost illustrates Thomas Griffiths Wainewright’s (1794-1847) spectacular fall from grace, from occupying the fine parlour rooms of nineteenth century England to hawking watercolour portraits thousands of miles away in a shed on the Hobart Rivulet. His life of misdemeanors inspired characters conjured by Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde, and in Paradise Lost viewers follow Wainewright’s journey through his work as a painter and portrait artist.

‘…beauty, excess and pleasure were at the forefront of Wainewright’s everyday life and work.’

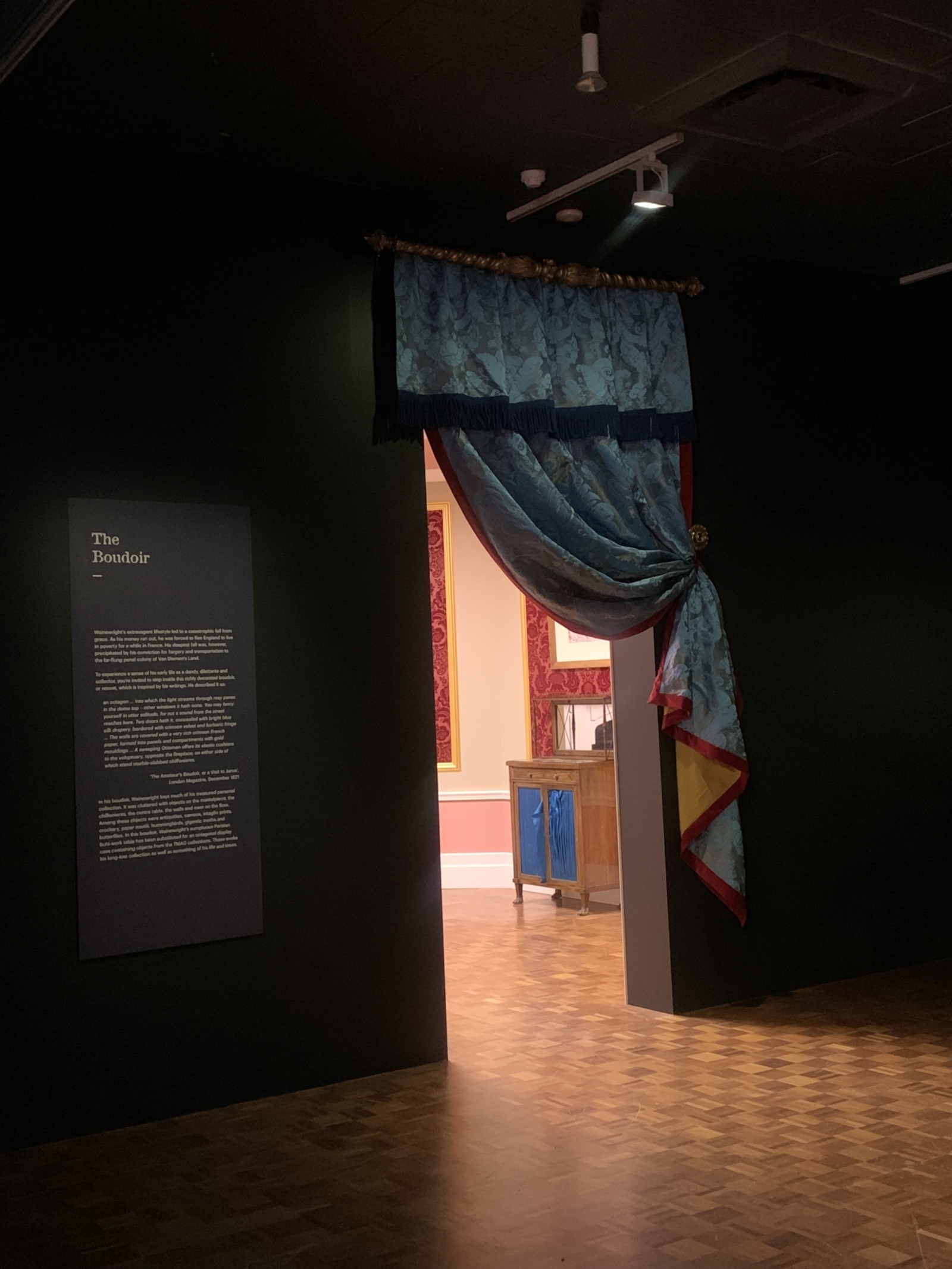

Presented in partnership with Dark Mofo, Paradise Lost covers four galleries in a series of visual chapters, with the first scene of the exhibition set in a lavishly decorated nineteenth century boudoir. A lush curtain is pulled across a doorway to reveal an octagonal room with a glass terrarium-style table filled with curios and antiques from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery collection – a knight’s helmet, atlas moths and ornamental teapots. Modeled after Wainewright’s actual domestic settings, it is clear from the start he was an aesthete. Born into a wealthy literary family in late 1700s London, Wainewright initially began his professional life as a writer and critic before undertaking apprenticeships with artists John Linnell and Thomas Phillips.

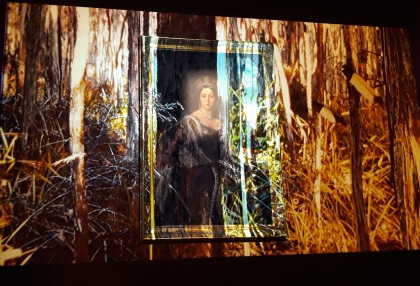

Moving through the exhibition, a collection of Wainewright’s oil paintings in the heady style of European Romanticism are accompanied by pieces created by those he admired. In particular, prints and paintings by William Blake and Henry Fuseli are prolific inclusions. At this point in time, Wainewright favoured narrative paintings drawn from myths, fairy tales and poetry, and an audio component by Archipelago Productions reveals further insight into this part of his life. Adding to the opulence of the oil paintings here are red velvet chairs, decorated pianos and well-stocked bookshelves. Tucked away in a room with restricted 18+ viewing is a series of raunchy illustrations by Edouard-Henri Avril. These excerpts from Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, or The Adventures of Fanny Hill were originally published in 1748 by Wainewright’s grandfather, Ralph Griffiths, who was also the founding editor of literary journal, The Monthly Review. It is clear that beauty, excess and pleasure were at the forefront of Wainewright’s everyday life and work.

Soon overwhelmed by an insatiable desire to own expensive and beautiful things, Wainewright began to rack up immense debt, eventually forging signatures to gain access to funds belonging to family and friends. He was suspected of poisoning several close relatives and sentenced to imprisonment on Van Diemen’s Land for forgery, leaving behind his wife and son in England. The third gallery in Paradise Lost reflects this turn of events as the visuals begin to shift from luxury to destitution, and Wainewright starts the transition from expensive oils to a limited palette of watercolour and pencil.

Mirroring the experience of most convicts in the nineteenth century, Wainewright’s life in Van Diemen’s Land was harsh, cold and physically demanding. After two years, Wainewright’s failing health gained him a position as convict wardsman at the Colonial Hospital in Hobart, where he became acquainted with members of the medical profession and their families. They were to become the subjects of many of Wainewright’s late portraits and the majority of these are clustered into the final gallery. To gain access to this gallery, viewers must walk through a structural repeat of the hexagonal boudoir from the beginning, only this time it is a sparse skeletal frame. Like walking free of a prison cell, viewers emerge into a room filled with faded, sepia toned watercolour portraits, a modest wooden bed frame and a weathered prison cell door from the 1830s.

Wainewright’s late portraits possess an ethereal quality with soft, wispy linework. In contrast to the grand narrative paintings of his youth, Wainewright now focuses on capturing the subtlety of facial features. Despite being restricted in materials, the simple execution of Wainewright’s watercolours expertly highlight the unique characteristics of his subjects – a wounded eye, sagging wrinkles or a cherubic grin. A reflection of his somber final days, this gallery contained personal items like an illustrated scrapbook and a walking cane. A theatrical visual treat from beginning to end, one of my favourite pieces in Paradise Lost was a tiny watercolour study of feathers, gifted by Wainewright to Elizabeth Sarah Hopkins. Positioned near the exit, these tiny feathers seemed to speak of a man who had come full circle – from excess to exile – ending his days (perhaps unwillingly) looking outwards rather than inwards.

BD

Briony Downes

Briony Downes is an arts writer based in Hobart. She is a regular contributor to Art Collector, Art Guide Australia and Art Edit.

Installation images of Paradise Lost and Henry Fuseli’s Study for the three witches in Macbeth, c. 1783.

Paradise Lost is a part of Dark Mofo 2021.

No Comments