Submitted Review

‘…tragic misreadings that have haunted Western and Islamic relations…’

‘I Weave What I Have Seen: The War Rugs of Afghanistan’

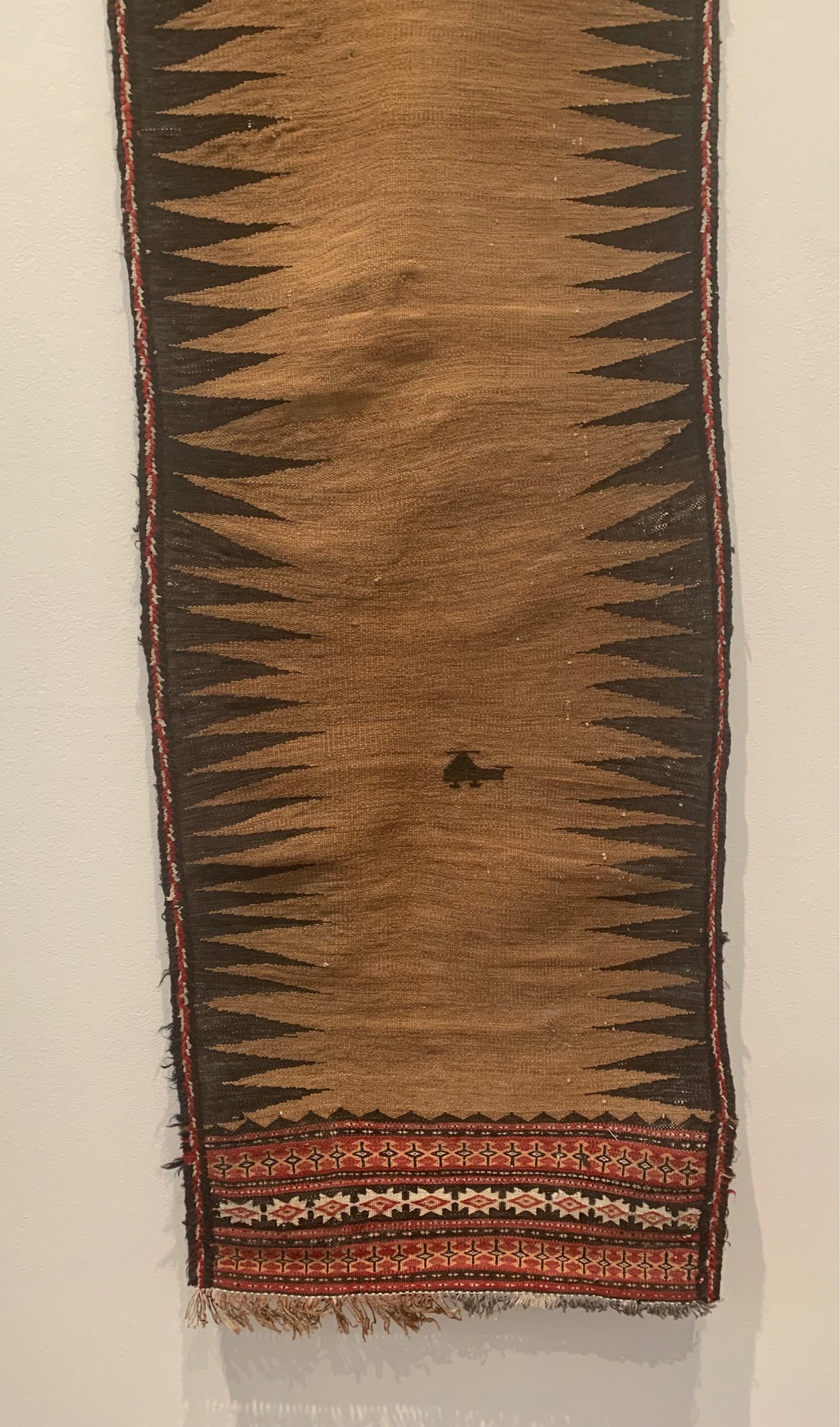

The first objects you encounter in I Weave What I Have Seen are a group of three modest kilims. Their iconography is so spare that it is easy to read them simply as abstracted symbols. One rug depicts what looks like a bird and a cooking pot, separated by a small curious blurred shape. A second rug is woven with three arrow-like emblems in a vertical row. The two are separated by a long runner. Along its length, narrow black chevrons extend from the sides into an empty and unadorned central space the colour of sand. Towards the bottom, a small object – an insect perhaps – hovers in the void. It takes a minute or two to realise that what you are looking at is a tiny helicopter. Once you do, you re-see what is encoded in the other two rugs: military aircraft, not arrows; tanks and missiles, not cook pots.

The exhibition is derived mainly from the extensive collections of its curators, Tim Bonyhady and Nigel Lendon, amassed over twenty years of their shared research into Afghan war rugs. It is hard to imagine a more apposite time for an exhibition such as this, coming as it does in the year the US and its allies are withdrawing from their twenty-year occupation of Afghanistan and when recent accusations of war crimes towards Afghani civilians have been levelled at Australian SAS forces.

The title of the exhibition is an injunction to bear witness, a responsibility shared by both the weavers and the viewers of the exhibition. Apart from the sparing use of clear didactic texts, the curators allow the rugs to literally speak for themselves in a narrative that positions the weavers as resourceful navigators of complex geopolitical and cultural forces.

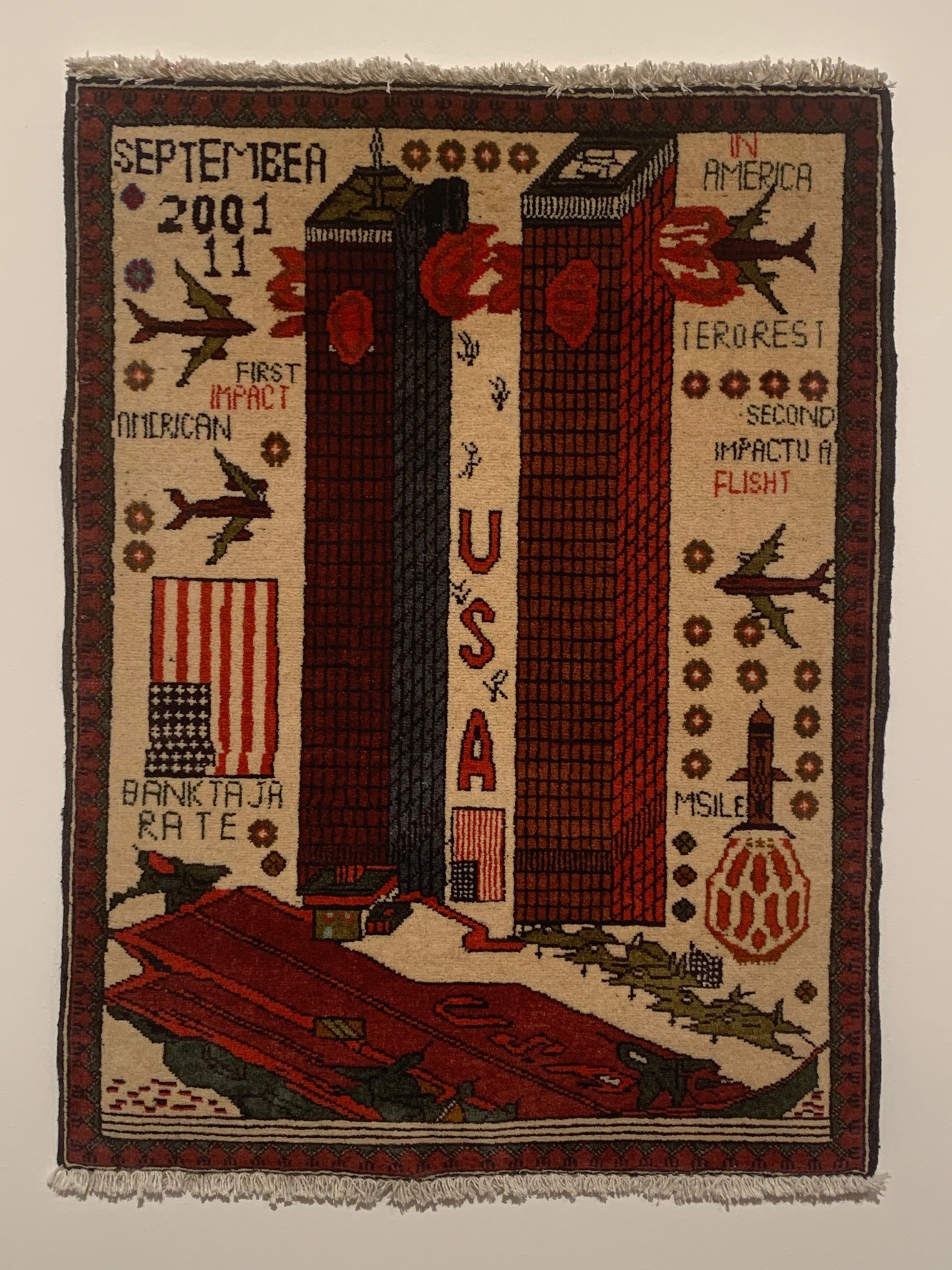

In the large central room of the Drill Hall Gallery, the judicious hang explores the myriad sources used by the weavers. Many of these, of course, are overtly political. Three fascinating rugs show how political posters from the 1980s were used to express opposition to the Soviet-imposed puppet governments of Afghanistan and were then – with some minor alterations to their iconography – re-purposed to critique the US invasion in 2001. Another grouping depicts a subgenre of rugs depicting maps of Afghanistan and political maps of Europe derived from Western atlases, bordered by friezes of flags and military armaments. In a smaller breakout room, two rugs depicting the destruction of the Twin Towers incorporate English words from Western press coverage: “USA”; “First Impact”; “Terrorest”; “Msile”, the imperfect transliterations of some of the words acting as unwitting metaphors for the tragic misreadings that have haunted Western and Islamic relations ever since.

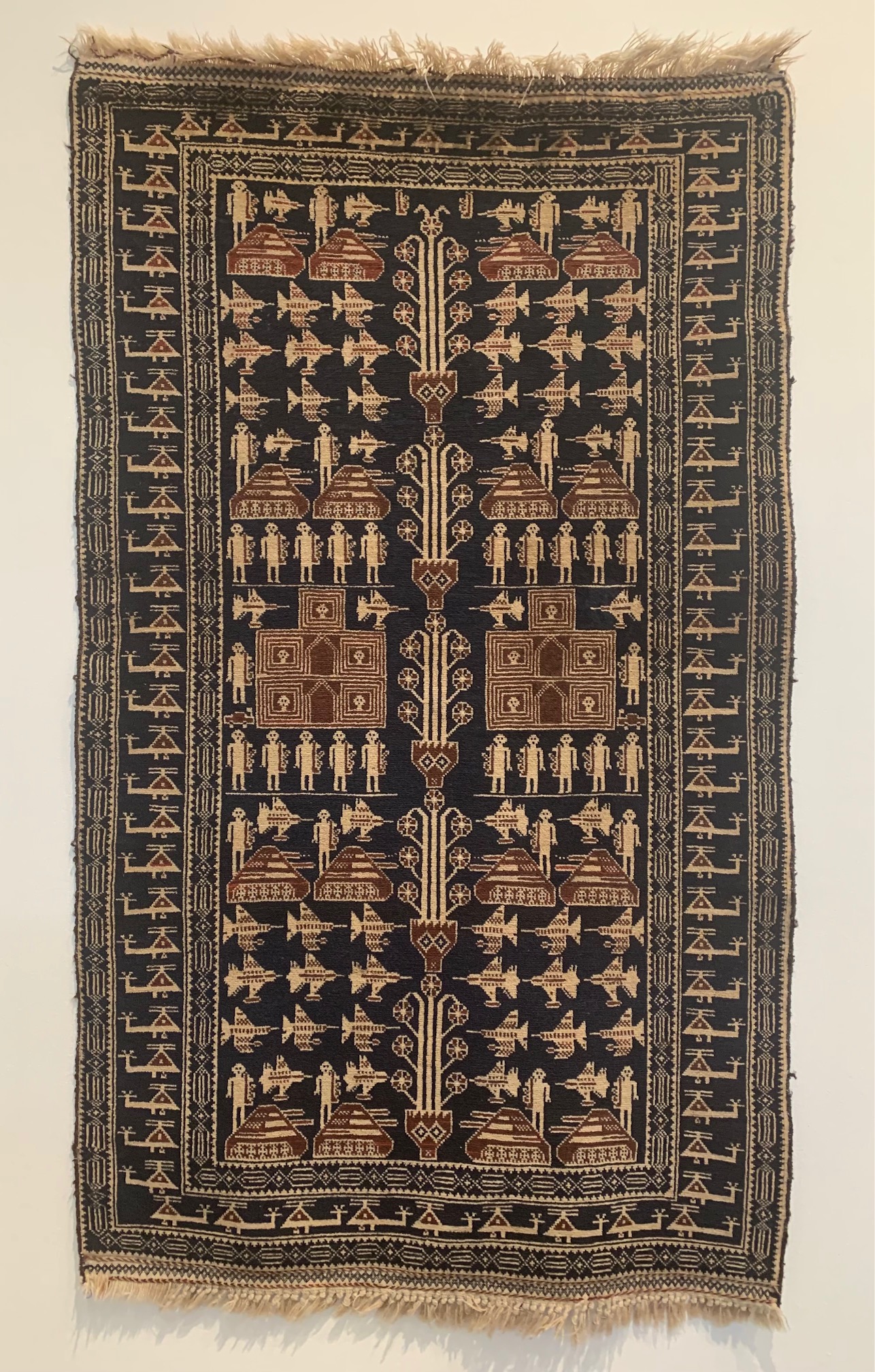

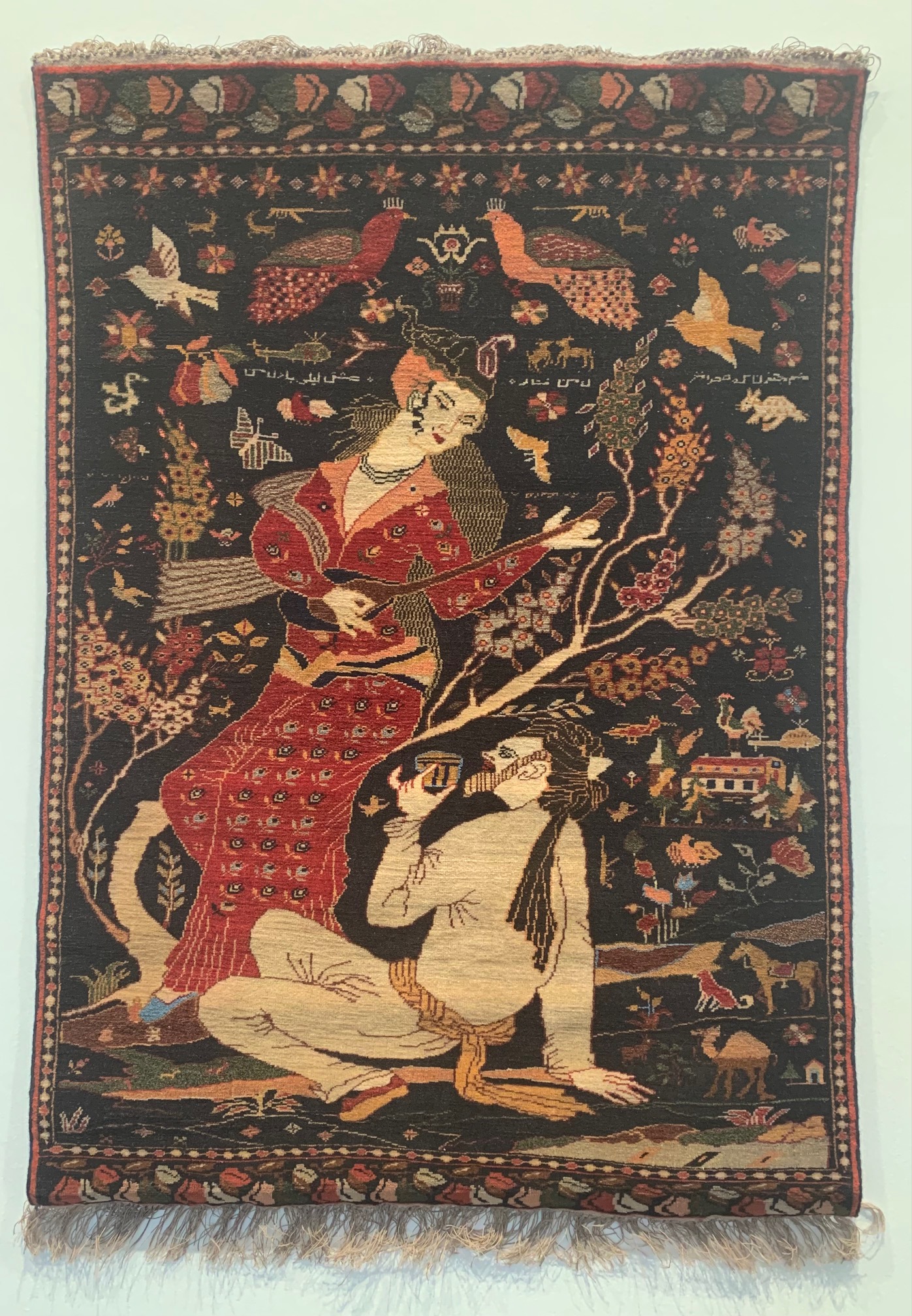

Perhaps the most interesting moments in the exhibition occur where the “timeless” spaces of tradition appear to collide with the temporal spaces of the present. Several rugs depict subjects more traditionally addressed by Afghani weavers: the ill-fated lovers Leyli and Majnun of 11th century Persian literature, for example. In one particularly striking rug, the two figures are depicted in a style recognisable from Persian miniatures, its traditional botanical and animal iconography interspersed with helicopters, planes and machine guns. In another more stylised version, Majnun is dressed in the outfit of a mujahideen, laden with weapons.

Sometimes these collisions occur at the borders, where the repeated bands of tanks, helicopters and Kalashnikovs are so stylised and embellished that they begin to lose their malign specificity and become simply another highly decorative frieze. In these moments we not only glimpse the way in which conflict has saturated and shaped the lived experience of contemporary Afghanis, but we also read how its contemporary experience has become a lens for understanding their cultural and political past.

No Comments