Submitted Review

Curated by Juliana Engberg ‘ALL THAT WAS SOLID MELTS’

‘…the fracture of personal narrative and inexorable acceleration of time.’

If the present moment has the unnerving effect of reducing each of us to so many statistics – “…specs in the cosmos…” – cast as hapless wanderers amongst successive plagues and calamities, then a timely exhibition such as “All That Was Solid Melts” reminds that this is a perennial not only of the vainglorious human condition, but that of the earth and all its creatures ultimately. Whilst its primary focus is on individual artistic responses across time, tremor and travails, a certain serious scholarly and literary mood prevails, many of the works as if signposts drawn from greater narratives.

Juliana Engberg, familiar to most from her persuasive and all-pervading curation at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art and other places over many years and currently Curator of International Art at Auckland Art Gallery, has collaged together a diverse mix of historical, international, and more ‘local’ artists from each side of ‘the ditch’ – many notable and familiar from her earlier curatorial work. As such, a number of Australian artists duke it out with contemporaries from New Zealand and further afield, cementing fruitful cross-Tasman and cross-continental dialogues, in an exhibition that meanders from the highly expressive through the deeply personal and onward toward the ineffable.

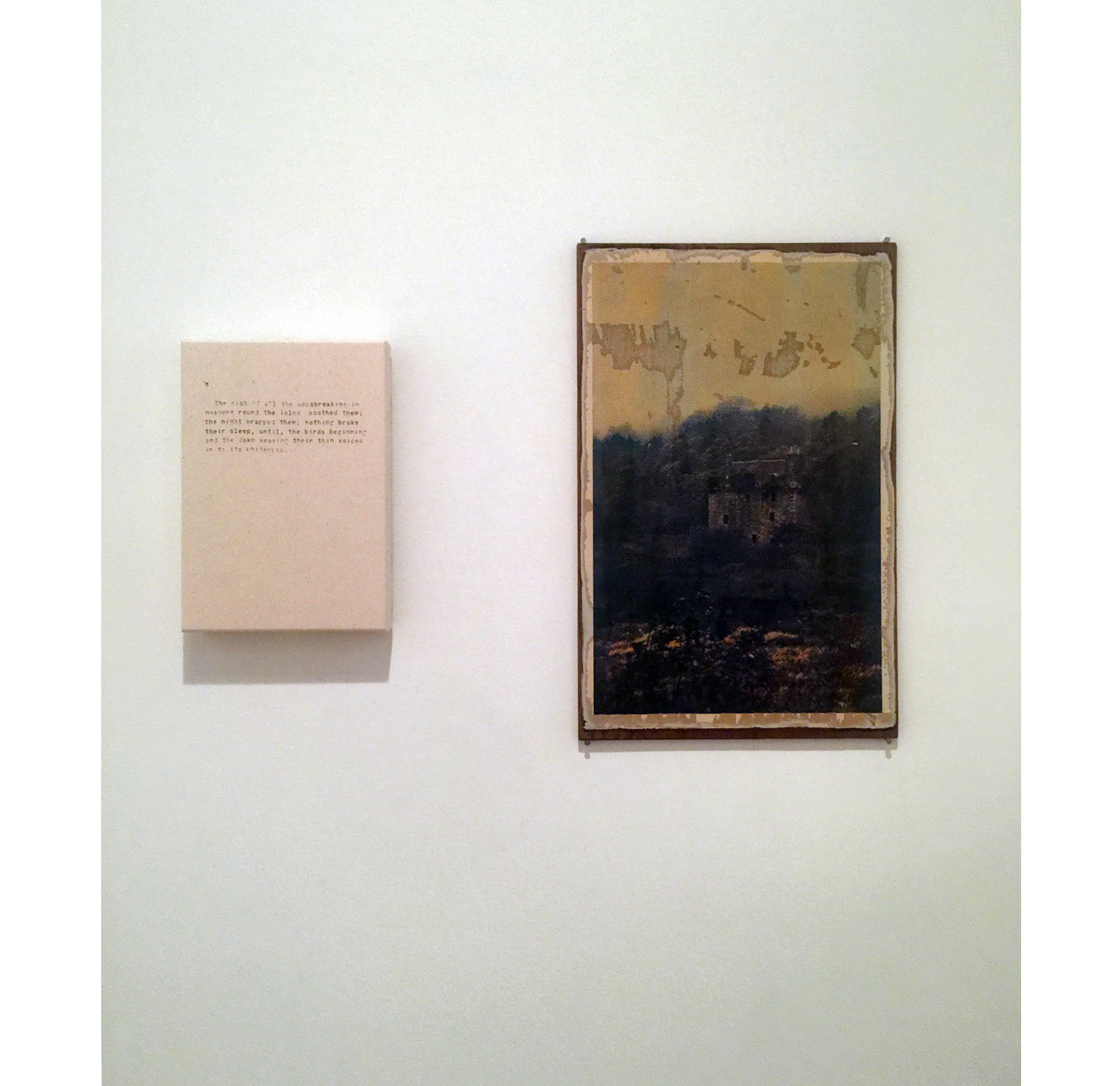

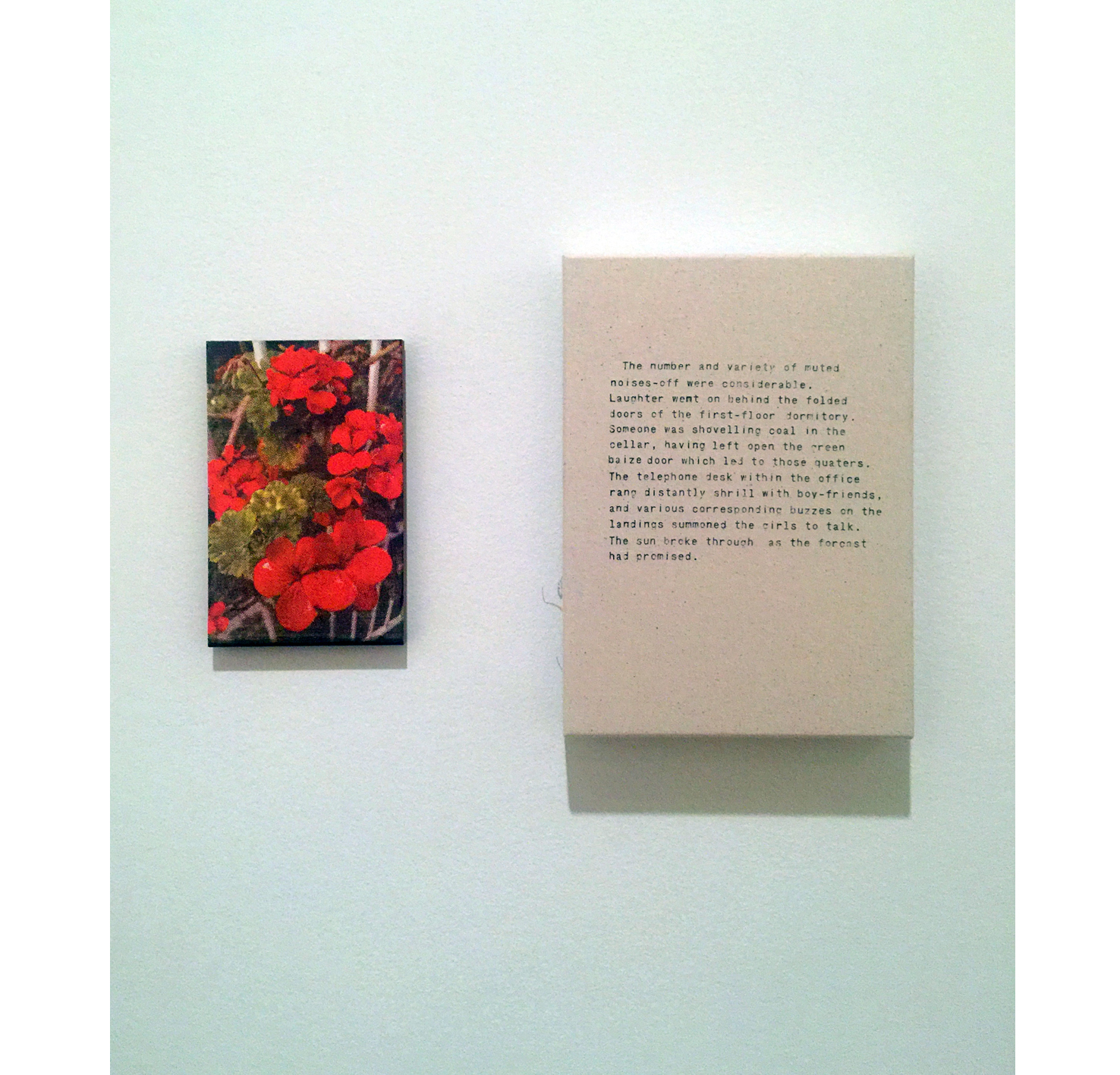

Alongside iconic works such as Pierre Huyghe’s “(Untitled) Human Mask” (2014) and Tacita Deans “JG” (2013) the handful of Australian artists make their own valuable contributions to Engberg’s premise. Peppered throughout the presentation – almost as intimate intervals – are the text and image works of the late Kate Daw. Extracts from female writers (Woolf, Mansfield as example) are juxtaposed with gently archaic landscapes and blooms, each juxtaposition of text and image briefly evoking a moment fast receding amongst the fracture of personal narrative and inexorable acceleration of time. If the pervasive imagery of ruins and and ruination throughout the exhibition becomes enervating, a pause before Callum Morton’s “Cover Up” (2021) – a shrouded and secretive panel, from an ongoing series – allows the mind to wander into more ambiguous realms, the minimalist form uncanny and mysterious, whilst also suggestive of hidden, obsolete or outmoded culture and its aspiration. Close by, a columned portrait of Dante’s muse Beatrice by U Biagiri (1900) is similarly swaddled, eyes cast down, holding her thoughts and feelings close, in a visual echo of Morton’s more determinably modernist form.

Amongst a room stuffed with Piranesi’s prints – depictions of richly decrepit and relatively de-populated architecture, Bill Henson’s listless and de-clothed youths in “Untitled” (1992-3) speak of love amongst the ruins, but one reduced to just so much role-play, as the shadows of mortality gather. From a series this writer had only passing regard for at the time of its premier, the seemingly off-hand placement of the figures in a believable yet abject landscape of wreckage has become increasingly persuasive – both as metaphor and as reportage.

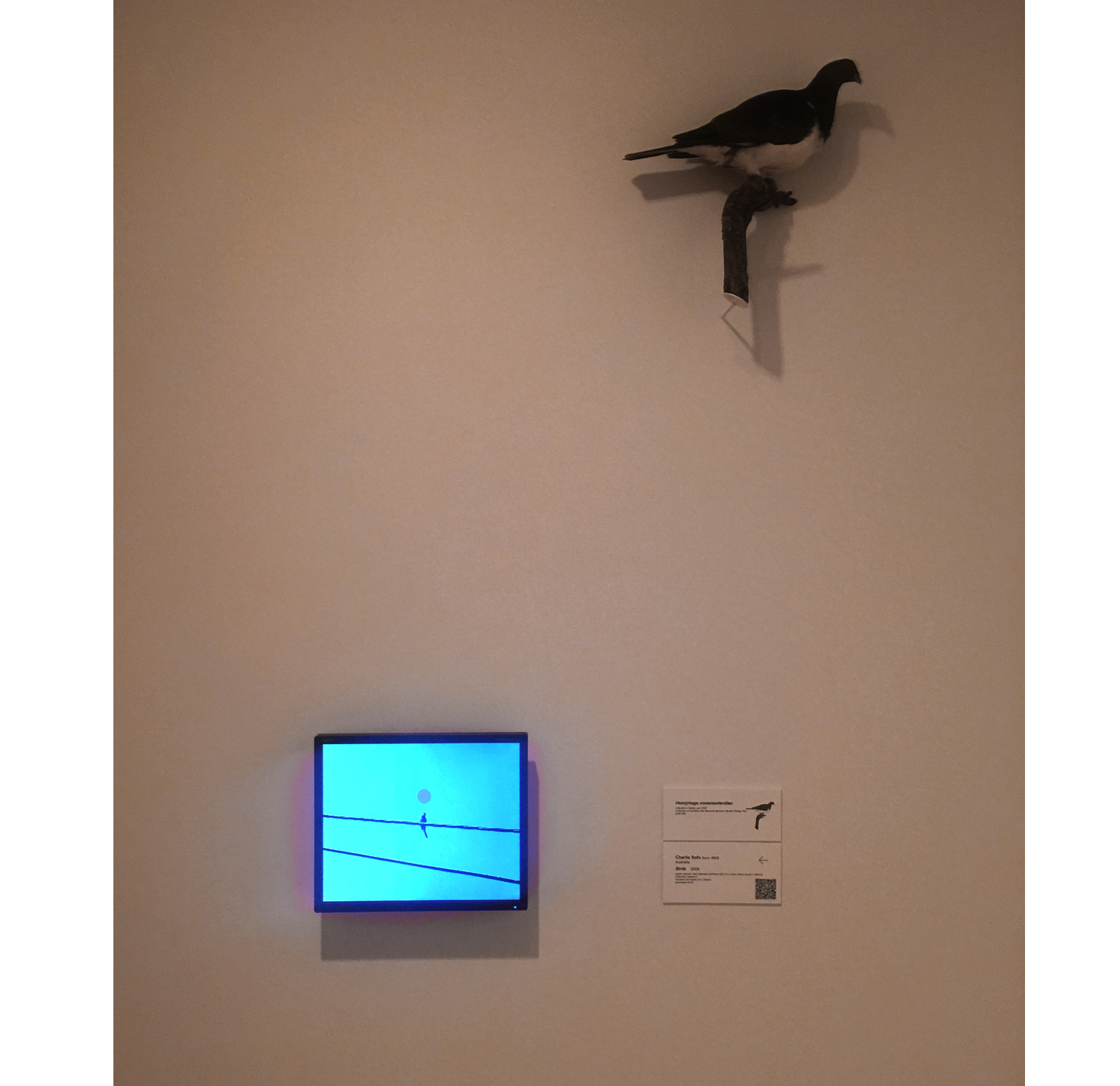

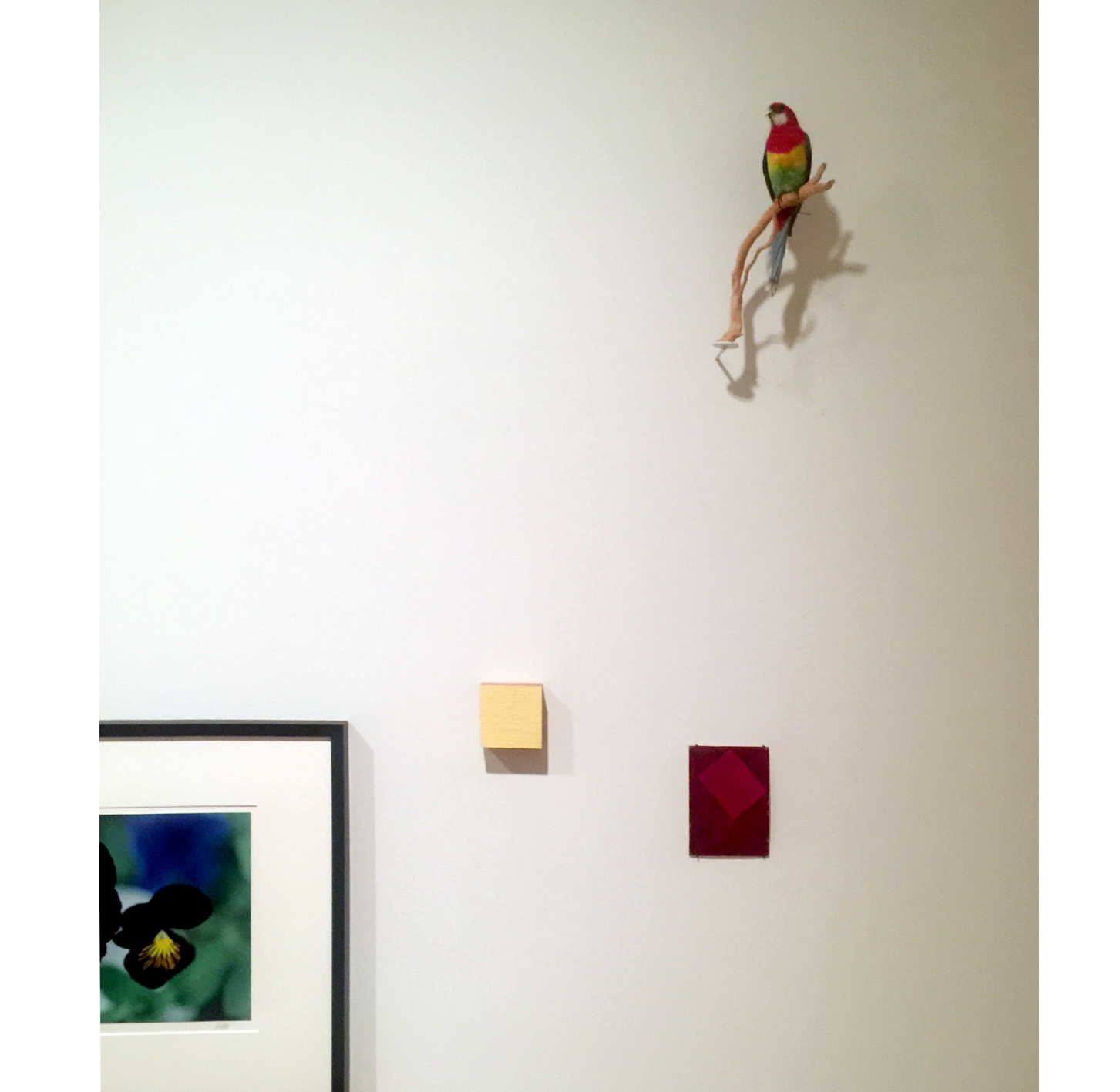

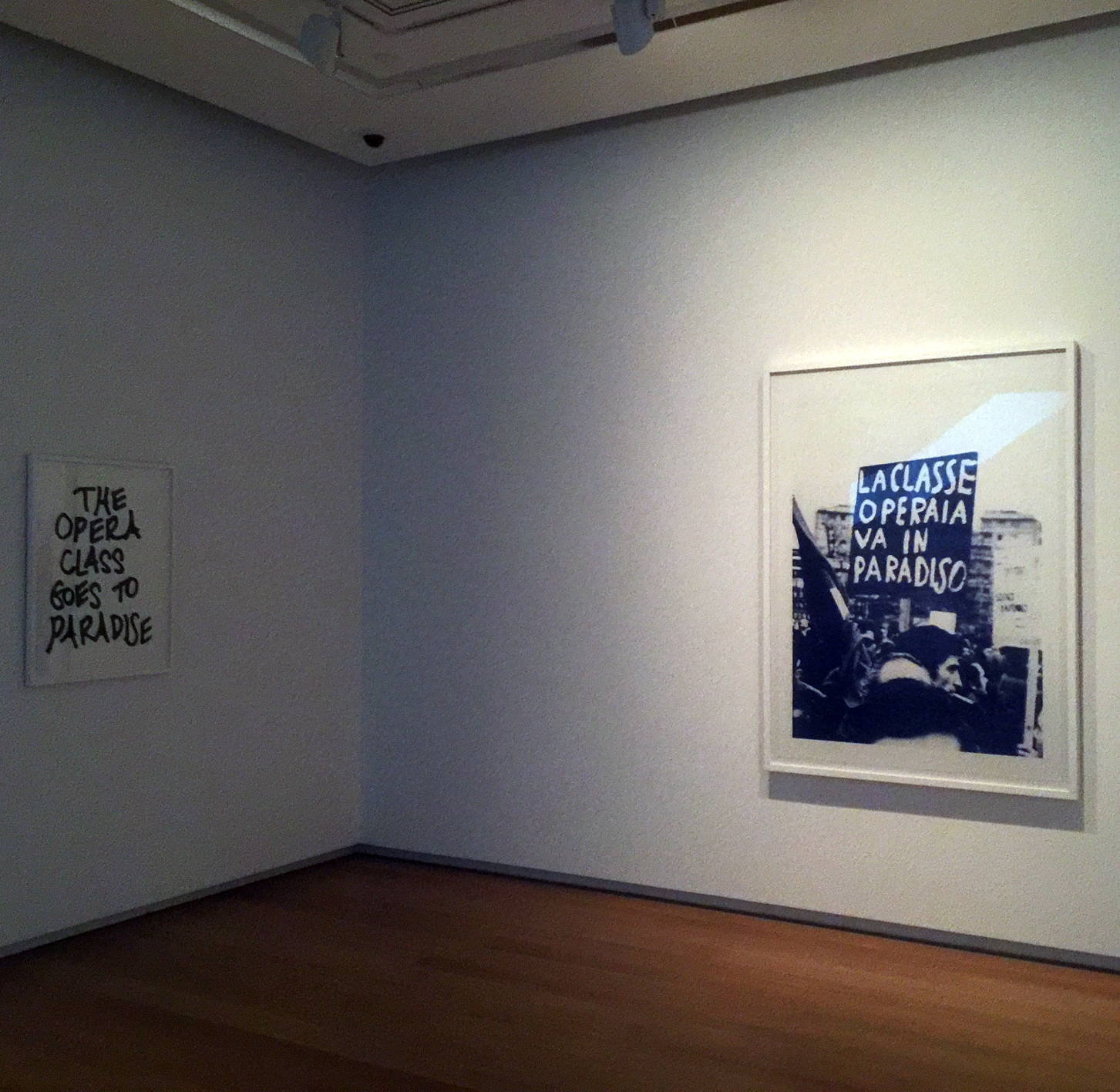

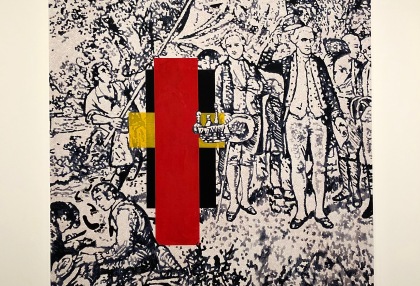

Various relics of the animal, natural and built worlds also feature (Paul Nash’s stunning “Landscape of Bleached Objects” circa 1934 one such), and the inclusion of John Nixon’s surgically small “Maroon Cross” painting amongst flower studies and stuffed birds casts it as relic rather than reliquary, its symbolism a collision of archaic and modernist faith – the cross a fixed point around which ideas, actions and intentions wax but also wane. Action is of course a key strategy to alter a course of events, even as greater forces conspire to derail the best or worst of intentions, and in Marco Fusinato’s “Rose #11” (2006) and his screen-print and gouache ‘posters’ we find the uncomfortable chill of action and reaction as he drills down on histories, democracies and discontents. Alternately, the inclusion of the affable and curious Charlie Sofo acts as some antidote to the prevailing down-beat tone of much work in the exhibition – his “Birds (stills)” video incorporating musical notes with bird sightings, resulting in a cheerful melody of avian visuals and ‘chance music’. As the curator Engberg notes, one of the few pleasures of recent difficulties has been the relative quietude of many peoples close environment, allowing for simple pleasures of unstructured musings and chance observation – birds figuring prominently often upon waking, and during walking.

With its smart juxtaposition of Oceanic and international art – many drawn from the Auckland Art Gallery collection – the curator has created a mirror of sorts…selective by necessity of course, but one that gestures in a highly effective manner toward the ever-complex, ever-evolving situations and events that time thrusts on us, as it also shapes us.

AB

Andrew Browne

*Note: Due to the relatively low light of museum standards, and my relatively old I-Phone, the quality and clarity of the photography here is pretty average – my apologies to all. AB

No Comments