Submitted Review

‘…drips remain like untrimmed threads, providing points for the viewer to enter these quiet conversations.’

Jude Rae ‘Jude Rae’

Still life that moves you.

The still lifes in Jude Rae’s solo exhibition at Philip Bacon Galleries in Brisbane can be seen as poignant mementos of the COVID-19 epoch. Many of the paintings were created during this challenging time of impromptu lockdowns and border closures sanctioned by the state governments.

Between the mid-1960s and early 2000s French post-structuralist Pierre Bourdieu described a tendency for people to fill their lives with the company of objects. This anthropomorphism has since been greatly accentuated. Jude Rae’s pared-back paintings are carefully composed with objects, drawn from the artist’s domestic vicinity. The canvases are human in scale.

The compositions invite discussion. In SL443, a coupling of a metal thermos and a clear glass bottle appears intimidated by a grouping of a hydrant valve, a plastic water cooler bottle and leaves of mother-in-law’s tongue. In SL447, fern fronds coyly reach for a fire extinguisher. There are rich, painterly areas with refined detail and areas left under-painted. In some instances, drips remain like untrimmed threads, providing points for the viewer to enter these quiet conversations. The raw areas of canvas also create a sense of temporality despite the robust materials of many of objects she depicts.

It is in subject matter that Rae is distinct from the pioneers of Australian modernist painting like Grace Cossington-Smith and Margaret Preston. The contribution of these women to Australian art during the interwar period was celebrated in the 1970s. Rae would have been coming of age during this second wave of feminism in Australia. Her paintings are rigorously devoid of florals arrangements that are usually expected in still life paintings by women.

The practice of painting onto unprimed canvas was engaged by modernists such as French Impressionists Edouard Manet and Eva Gonzalès. This is likely to have been influenced of Japanese culture, which catalysed change in the subject matter and compositional conventions of nineteenth century European art. Painting onto un-primed canvas was also a feature of the Colour Field movement, with artists like Mark Rothko similarly engaging the technique. In their compositions, like Rae’s, the materiality of the paint, like a ‘skin’ on the canvas, was emphasised. But unlike the modernists, Rae investigates the ‘imagined’ or immaterial through perforating this membrane of constructed reality. The focus of the materiality of the paint, during the nineteenth century, may have also reflect the art and craft movement in Europe and North America.

Rae exercises exceptional skill in the application of paint: her objects materialise through its addition and removal. Her compositions are carefully constructed using an analytical approach inspired by the post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne. There is an emphasis on painting the light, but here it is controlled by artificial sources. Whilst the objects are defined with realist precision, the spaces in between are expressionistic, immersive and tactile. Accentuated by a vibrant yet calming palette, with contrasts between cool coloured metallic surfaces and warm tonal backgrounds, Rae’s still lifes appeal as places of refuge from the COVID related chaos.

The variation in the objects that the artist selects – from mass produced, everyday items like gas cylinders to hand-crafted vessels and organic forms – also provides a critique on late twentieth and early twenty-first century materialism. In one of the compositions, SL446, a vessel that appears to be an oriental vase sits apart from the other objects. It is reminiscent of the Dutch vanitas created during the seventeenth century against the backdrop of bubonic plague outbreaks. Despite a lack of opulence, the objects appear to originate from a diversity of geographic locations. This is a reminder that objects continued to be imported in a time when travel was restricted.

There is a preciousness in the way Rae has depicted the ordinary, particularly manufactured items like the white plastic bucket. Rae’s childhood and adolescence in the 1960s and 1970s saw a burgeoning of mass production with the advent of computer numerical control (CNC) milling or subtractive manufacturing. Objects were either cast from moulds produced using this technology or directly machined using it. It is this devotion to analogue methods of creating images of digitally manufactured objects that situates her artwork in the post-digital early twenty-first century.

Abstraction and still life have both been characteristic of resistance and internalisation during adverse political climates in both Asian and European art. During the Yuan Dynasty (1271 –1368 CE), for example, despite having achieved a high degree of technical realism during the Song Dynasty (960 –1279 CE), the Chinese literati turned to abstract painting in defiance of the Mongol occupation. Dutch neo-plasticist Piet Mondrian sought to create unity through his colourful geometric compositions amidst the disharmony of the interwar period. Similarly, the contemplative vessels of the modern realist painter Giorgio Morandi have been interpreted as his response to the rise of Fascism in Italy.

These historical precursors serve to enhance the gravitas of this exhibition, despite the presence of both genres in Rae’s practice that pre-date the pandemic. The paintings reflect the comfort sought in objects. From fire extinguishers to milk pitchers, they are by and large vessels. Their capacity to create sites of contemplation as opposed containment is investigated. The subsequent environments appear inhabited by the zeitgeist of the COVID-19 epoch.

PMS

Pamela See

Images courtesy Pamela See and Philip Bacon Gallery, Brisbane.

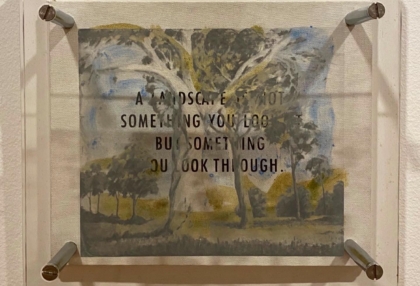

Images 1-2: Installation.

Image 3: Jude Rae, SL443, 2021, oil on linen, 112 x 137.5cm.

Image 4: Jude Rae, SL447, 2021, oil on linen, 122 x 137.5cm.

Image 5: Installation with SL446,2021, oil on linen, 122 x 137.5cm.

No Comments